This FAQ zine is meant to be a starting point. It’s short, and shares the basics of what we’re talking about when we talk about abolition. It’s been a very useful tool for sparking conversations with people who haven’t considered these ideas before.

A potential next step after reading the FAQ: What are we talking about when we talk about “a police-free future?”, as well as much more at our Resources page.

The text below is also available in different formats, so that people can print/share:

- English One-Sheet Handout (updated for 2020)

- English/Spanish/Somali One Sheets Handouts

- 8-page zine – directions for how to cut/fold here

- Page by page

- Instagram post

- Haga clic aquí para español

- “Police Abolition 101” resource that greatly expands on this FAQ.

~~~

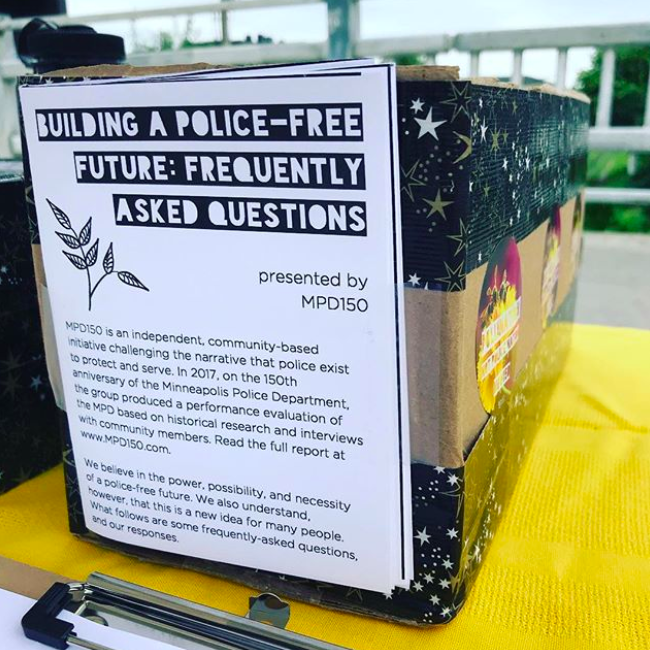

Building a Police-Free Future: Frequently-Asked Questions

We believe in the power, possibility, and necessity of a police-free future. We also understand, however, that this is a new idea for many people. Here are some frequently-asked questions, and our responses to them.

Won’t abolishing the police create chaos and crime? How will we stay safe?

Abolition is not about snapping our fingers and instantly defunding every department in the world. Rather, we’re talking about a process of strategically shifting resources, funding, and responsibility away from punishment and toward prevention; away from police and prisons and toward the systems and services that support real wellness and safety—human needs like housing, child care, health care, and beyond.

The people who respond to crises in our community should be the people who are best-equipped to deal with those crises. Rather than strangers armed with guns, we want to create space for more mental health service providers, violence prevention specialists, social workers, victim/survivor advocates, elders and spiritual leaders, neighbors and friends—all of the people who really make up the fabric of a community—to look out for one another. For some real-world models of what this can look like, check out the “abolition in practice” section on our Resources page.

But what about armed bank robbers, murderers, and supervillains?

Crime isn’t random. Most of the time, it happens when someone has been unable to meet their basic needs through other means. So to really “fight crime,” we don’t need more cops; we need more jobs, more educational opportunities, more affordable housing, more arts programs, more community centers, more mental health resources, and more of a say in how our own communities function.

Sure, in the transition process, we may need a small, specialized class of public servants whose job it is to respond to violence. But part of what we’re talking about here is what role police (and the billions of dollars we invest in them) play in our society. Right now, only a small fraction of police work involves responding to violence; more often, they’re making traffic stops, arresting petty drug users, harassing Black and Brown people, and engaging in a range of “broken windows policing” behaviors that only serve to keep more people under the thumb of the criminal justice system.

Abolitionists don’t want to abolish help. We should all have someone to call on when we need to. We also don’t want to abolish consequences; no one is saying that people who harm others should just be ignored or allowed to do whatever they want. But the bigger picture is that for far too long, police have been used as a one-size-fits-all “solution” to every social problem, and that approach just doesn’t work.

But why not fund the police and these alternatives too? Why is it an either/or?

It’s not just that police are ineffective: in many communities, they’re actively harmful. The history of policing is a history of violence against the marginalized— U.S. police departments were originally created to protect the interests of the wealthy, white elite, and racialized violence has always been a part of that mission. Historically, “serve and protect” has simply not included Black, Indigenous, and people of color, the disabled, the poor, the undocumented, LGBTQ communities, and beyond.

And it’s bigger than just police brutality. It’s about how the prison industrial complex, the drug war, immigration law, and the web of policy, law, and culture that forms our criminal justice system has destroyed millions of lives and torn apart families. Cops don’t prevent harm; they cause it, through the ongoing, violent disruption of our communities.

It’s also worth noting that most social service agencies and organizations that could serve as alternatives to the police are underfunded, scrambling for grant money to stay alive while being forced to interact with officers who often make their jobs even harder. In 2020, the Minneapolis Police Department received $193 million in city funding alone. Imagine what that kind of money could do to keep our communities safe if it was reinvested.

Even people who support the police agree: we ask cops to solve too many of our problems. As former Dallas Police Chief David Brown said: “We’re asking cops to do too much in this country… Every societal failure, we put it off on the cops to solve. Not enough mental health funding, let the cops handle it… Here in Dallas we got a loose dog problem; let’s have the cops chase loose dogs. Schools fail, let’s give it to the cops… That’s too much to ask. Policing was never meant to solve all those problems.”

What about body cameras? What about civilian review boards, implicit bias training, and community policing initiatives?

Video footage (whether from body cameras or other sources) wasn’t enough to get justice for Philando Castile, Samuel DuBose, Walter Scott, Tamir Rice, and far too many other victims of police violence. A single implicit bias training session can’t overcome decades of conditioning and department culture. Other reforms, while often noble in intention, simply do not do enough to get to the root of the issue.

History is a useful guide here: community groups in the 1960s also demanded civilian review boards, better training, and community policing initiatives. Some of these demands were even met. But universally, they were either ineffective, or dismantled by the police department over time. Recent reforms are already being co-opted and destroyed: just look at how many officers are wearing body cameras that are never turned on, or how quickly the Trump administration’s Justice Department moved to end consent decrees. We have half a century’s worth of evidence that reforms can’t work. It’s time for something new.

This all sounds good in theory, but wouldn’t it be impossible to do?

Throughout US history, everyday people have regularly accomplished “impossible” things, from the abolition of slavery, to voting rights, to the 40-hour workweek, and more. What’s really impossible is the idea that the police departments can be reformed against their will to protect and serve communities whom they have always attacked. The police, as an institution around the world, have existed for less than 200 years—less time than chattel slavery existed in the Americas. Abolishing the police isn’t impossible—we can do it in our own cities, one dollar at a time, through redirecting budgets to common-sense alternative programs. Let’s get to work!

I still have questions. Where can I learn more?

We encourage people to check out writing from scholars and activists like Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Mariame Kaba, and others who have been writing about abolition for years. Two potential starting points:

1. The “Resources” page at www.MPD150.com is full of links: articles, essays, and book recommendations that go more in-depth on these questions and others.

2. “Enough Is Enough: A 150-Year Performance Review of the Minneapolis Police Department.” Newly released, this expanded version of our 2017 report features historical research, interviews with advocates and service providers, an exploration of alternatives, and much more. The report is available for free (read online or order physical copies) at www.MPD150.com.

Finally, for people in Minneapolis who want to get involved in building our police-free future, be sure to check out our “sunsetting reflections” page.