An initial note: we encourage people to check out the PDF of the new, revised, expanded version of our report. These pages will be brought up into alignment with that, but it may take some time.

Supporting Content

The Past section of the report is supported by various articles on our Timeline. As you are reading, if you come across a section noted with “(!)“, please feel free to explore the longer article on the specific topic in the Timeline.

Past

The City of Minneapolis wasn’t formally established until 1867. Its first leader practically begged for a police force to oversee, saying “a mayor without a police force to appoint and regulate would hardly feel that he was Mayor.”1Kristian Williams, Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America (Baltimore: AK Press, 2015), 75-77. The city council agreed, and on March 9th, 1867, the first four officers were appointed to the Minneapolis Police Department. It’s important to note the historical context here: the Minneapolis Police Department was established less than 30 years after Dred Scott and his wife Harriet were held as slaves at Fort Snelling,2“Slavery at Fort Snelling (1820s – 1850s),” Historic Fort Snelling, accessed November 03, 2017, http://www.historicfortsnelling.org/history/slavery-fort-snelling. only five years after the hanging of 38 Dakota men at the hands of the U.S. government following the U.S. Dakota War of 1862, only two years after the end of the Civil War. Perhaps, given the department’s beginnings, the history that was to follow was predictable.

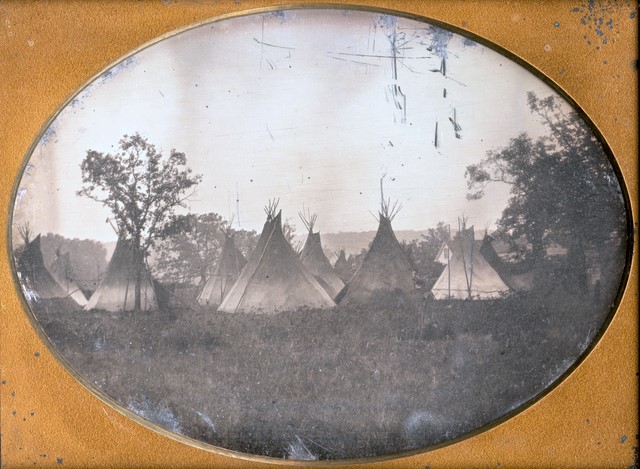

In this section of the report, we will examine that history from its beginning,

Circa 1852, a Dakota Community located at what is now approximately Hennepin Ave. and S 2nd St. in downtown Minneapolis

starting with the origins of the concept of policing itself. We’ll look at the first fifty years of the Minneapolis Police Department, and the department’s early history as a corrupt political tool. Then we’ll move into the middle years, 1918 – 1967, and MPD’s increasing violence towards Black and Native communities, immigrants, union members, and other marginalized groups. Finally, we’ll look at the most recent fifty years – a time of disgrace, militarization, and countless failed reforms at the Minneapolis Police Department.

Over the past year and a half, we’ve written a collection of more than twenty short pieces on particularly illustrative stories from MPD’s history. These pieces served as the basis for the incomplete history we’re going to tell here. If you’re interested in learning more about a particular incident in this section, and it has a (!) next to it, that means there’s a longer piece about it, including citations, on the timeline below.

Undeveloped: The Origins of Policing

We often talk about police as if they’ve existed for all of human history, when in reality they’re a relatively recent invention. The first modern police force in the world was established in England in the 19th century – before that, communities were largely kept safe by informal institutions. In 1829, growing levels of property crime caused by urbanization and the creation of urban poverty led to the creation of a police force in London – the Metropolitan Police Department.3Kristian Williams, Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America (Baltimore: AK Press, 2015), 59. Home Secretary Robert Peel was the creator of the department, and based it on the model of the Royal Irish Constabulary, a “peacekeeping” force designed to maintain British rule and control rebellious communities in occupied Ireland. From their very beginnings in London, police departments were rooted in colonialism and the protection of property – policing’s origins in the United States, though, are even darker.

Though the 13 colonies imported a system of elected sheriffs and constables, who were empowered to enforce some laws, formalized American policing really began with slave patrols. Made up of local militias and slaveowners who patrolled the countryside stopping Black people and forcing escaped slaves back into bondage, slave patrols enforced white supremacy from some of the earliest days of the European occupation of the Americas. These patrols (and their Northern equivalents, town watches) were empowered to enforce curfews against Black and Native folks, search and confiscate their property, and brutalize them, with or without cause.4Kristian Williams, Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America (Baltimore: AK Press, 2015), 74. These groups were gradually granted additional powers and jurisdiction, eventually evolving directly into modern police departments. One example of this can be seen in Charleston, South Carolina, where a town watch created in 1671 for the explicit purpose of keeping Native and Black people in line eventually turned into the city’s first police department.5Ibid. 75 – 77.

Unprofessional: MPD, 1867 – 1917

In its early years, the Minneapolis Police Department grew rapidly, with each new mayor appointing more officers to the police force as the city population skyrocketed. At the time, mayors were elected annually, and often the entire police department would change every year as the new mayor fired their political opponents and appointed their friends, family, and political supporters to police jobs,6Michael Fossum, History of the Minneapolis Police Department, (Minneapolis, Minn.: s.n., 1996), 1. a common practice across the country at the time.7Kristian Williams, Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America (Baltimore: AK Press, 2015), Chapter 3. These early police were completely untrained, didn’t wear uniforms, and drank on duty so often that in 1875, the city council ordered the mayor to prohibit police from entering saloons while on duty except for when they were conducting official business.8Augustine Costello, History of the Fire and Police Departments of Minneapolis (Minneapolis, MN: The Relief Association, 1890), 252. Often the laws that were enforced changed from year to year as well, particularly those around sex work: although brothels were mostly allowed to operate without too much trouble, the first fines were imposed upon “the women of the town” in 1878. In the first year alone, the city collected $3470 in fines from sex workers (more than $80,000 in 2017 dollars).9Augustine Costello, History of the Fire and Police Departments of Minneapolis (Minneapolis, MN: The Relief Association, 1890), 261.

The city workhouse was completed in 1886. Though the 13th amendment, ratified in 1865, had prohibited chattel slavery, it had allowed for involuntary servitude “as a punishment for crime,”10U.S. Constitution, Amendment XIII and the city made huge profits out of that loophole. The city forced inmates to do a variety of work, including farming, making clothing, and working in the city quarry. In the first four years alone, the city made almost $9,000 ($244,000 in 2017 dollars) from inmate labor.11Minneapolis Police Department, 1872 – 1973: 101 Years of Service (1973), 8. Early Minneapolis had even more brutal ways of dealing with crime, too: the city’s first hanging was held in 1882.12Ibid., 9.

By 1889, the police force had grown to 169 uniformed officers patrolling a city of 200,000 people.13Michael Fossum, History of the Minneapolis Police Department, (Minneapolis, Minn.: s.n., 1996), 3. That year, tensions between industrialist Thomas Lowry and streetcar workers erupted into a massive fifteen day strike, with strikers and strikebreakers brawling for control of the streets. The Minneapolis Police Department came down hard on the strikers, arresting dozens and helping Lowry break the strike while avoiding offering any concessions to his workers. (!)

Downtown Minneapolis circa 1900

By 1900, Doctor A. A. Ames had been elected to his fourth term as mayor of Minneapolis. Unlike in his first three terms, this time Ames decided to use his political power for personal gain. He appointed his brother, Fred Ames, to be the chief of police, and quickly turned the Minneapolis Police Department into one of the most effective tools for corruption in the city. Under Ames, MPD officers committed graft, extortion, and burglaries, finally being stopped by a group of civilian activists in 1902. MPD wasn’t the only bad department at the time – many early police departments were deeply complicit in corrupt political machines14Kristian Williams, Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America (Baltimore: AK Press, 2015), 89 – 100 – but it did become infamous across the nation for the boldness of its crimes. (!)

The department continued developing into the 20th century: in 1902, five police precincts were established, and in 1909, the department bought its first paddy wagon, which helped the department round up “undesirables” under the state’s recently passed vagrancy laws.15Michael Fossum, History of the Minneapolis Police Department, (Minneapolis, Minn.: s.n., 1996), 4.

At the turn of the century, MPD often used its increasing power on behalf of the Citizen’s Alliance, a far right group of powerful businessmen established in 1903. The Citizens’ Alliance used MPD to harass, infiltrate, and attack labor groups, preventing them from building political power and organizing unions.16William Millikan, A Union against Unions: the Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and its Fight against Organized labor, 1903-1947 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001), xxvii. The 1889 streetcar strike had provided one example of how to use violence to force workers into obedience, and the 1909 Machinists’ Strike provided another: police protected strikebreakers as they crossed picket lines, and helped to crush the strike without any compromise on behalf of employers.17Ibid., 37. Despite their frequent mobilization against labor organizers, Minneapolis police officers established their own union, the Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis, in 1916,18“History,” Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis, accessed November 01, 2017, http://www.mpdfederation.com/about-us/history/. and were eventually welcomed into the American Federation of Labor.19William Millikan, A Union against Unions: the Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and its Fight against Organized labor, 1903-1947 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001), 206.

As the Minneapolis Police Department drew close to its 50 year anniversary in 1917, the department numbered more than 300 officers, without training, exerting power and control over a city of more than 300,000 residents.20Michael Fossum, History of the Minneapolis Police Department, (Minneapolis, Minn.: s.n., 1996), 12.21“Minneapolis, Minnesota Population History 1880 – 2016.” Minneapolis, Minnesota Population History | 1880 – 2016. October 3, 2017. Accessed October 31, 2017. MPD had made the city a lot of money, shut down several massive strikes, and been deeply implicated in the corrupt administration of Mayor Ames. If anything, the next fifty years would be even worse.

Unrestrained: MPD, 1917 – 1967

The Minneapolis Police Department became larger, more sophisticated, and increasingly brutal as the 1920s approached. By this time, the Citizens’ Alliance was a deeply entrenched force in Minneapolis politics, and they continued to use MPD and other law enforcement agencies to push their anti-union agenda. In 1917, supposedly looking to support troops fighting in World War I, the Citizen’s Alliance formed their own private army, fully supported by local law enforcement. When another streetcar strike broke out in 1917, the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office quickly deputized the private army and deployed it onto Minneapolis’ streets. With the Citizens’ Alliance troops armed with rifles and bayonets, the strikers didn’t stand a chance, and were quickly defeated.22William Millikan, A Union against Unions: the Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and its Fight against Organized labor, 1903-1947 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001), 125-126.

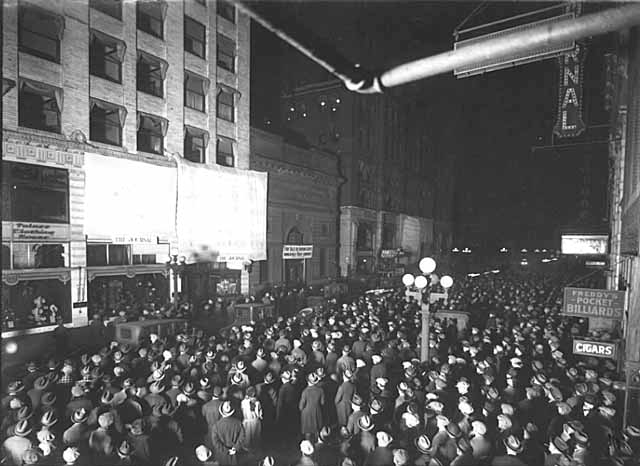

A crowd in downtown Minneapolis eagerly awaits the 1920 mayoral election results.

In other arenas of community control, the Minneapolis Police Department was much less effective: during prohibition (1920 – 1933), MPD attempted to arrest community members for possession of alcohol, but was often held back by the Minnesota Supreme Court. The Court refused to uphold convictions of alcohol possession; only those directly involved in the sale of liquor were punished.23Michael Fossum, History of the Minneapolis Police Department, (Minneapolis, Minn.: s.n., 1996), 4.

Meanwhile, a deep and unrelenting strain of white supremacy was growing stronger in Minneapolis and across the state. The Klu Klux Klan established more than fifty chapters across Minnesota beginning in 1917, and a growing Black population in Minneapolis was subject to racism of many varieties.24Johnson, Kay. “When the Klan came to Minnesota.” Crow River Media, (October 24, 2013) Accessed November 01, 2017. http://www.crowrivermedia.com/hutchinsonleader/news/lifestyle/when-the-klan-came-to-minnesota/article_a08b3390-cf3d-5419-afc6-486ac0e63475.html. Police brutality was a constant threat to the Minneapolis Black community of the 1920s.

On June 20th, 1922, MPD officers savagely beat and arrested four men for allegedly inviting some white women to a dance. That same day, an officer tried to shoot a Black man in the Mill City district after he refused to “move on,” only to be disarmed by the man, who ran from the scene with the officer’s gun. Members of the Black community, notably the Minneapolis NAACP, mobilized to demand reform of the Minneapolis Police Department. The calls for police accountability were largely ignored, and racism in MPD continued to be a major problem. (!)

The Citizens’ Alliance continued to mold the Minneapolis Police Department into a more effective tool to do their bidding; in the mid 1920s, they waged a public relations war against the police union, pressuring officers to say whether their loyalties lay with the American Federation of Labor or the city government. In 1926, the police union severed their ties once and for all with the national labor movement, a separation that remains to this day.25William Millikan, A Union against Unions: the Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and its Fight against Organized labor, 1903-1947 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001), 206 – 207.

The late 1920s led to other changes in the department as well; the first MPD training ever was held in 1929, 62 years after the establishment of the department.26Minneapolis Police Department, 1872 – 1973: 101 Years of Service (1973), 29. The training was indicative of a larger trend across the country: professionalization, where police departments worked hard to establish the idea that they were the foremost experts on crime prevention in the community.27Kristian Williams, Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America (Baltimore: AK Press, 2015), 212. At the time the entire police academy consisted of a day or two of lectures – hardly enough to make anyone a professional.

One thing the police were experts at was fighting labor movements, and they had another chance to demonstrate their skills in the 1930s. In 1934, five years into the Great Depression, unions were starting to gain a foothold in Minneapolis. On May 16th, 1934, thousands of truck drivers went on strike as part of the Teamsters union, leading to months of protests, negotiations, and street fighting in Minneapolis. In response, the Minneapolis Police Department, along with the Hennepin County Sheriff, deputized hundreds of civilians aligned with the Citizens Alliance and encouraged them to use violence against strikers. The deputies were poorly trained and armed, though, and were defeated by the strikers in a massive battle downtown. This didn’t stop MPD from trying to end the strike; on July 20th, they ambushed a group of 70 strikers, shooting them in the back with shotguns as they ran away and killing two of them. In the end, the strikers won the right to form a union, and the Minneapolis Police Department’s streak of successfully crushing strikes was broken. (!)

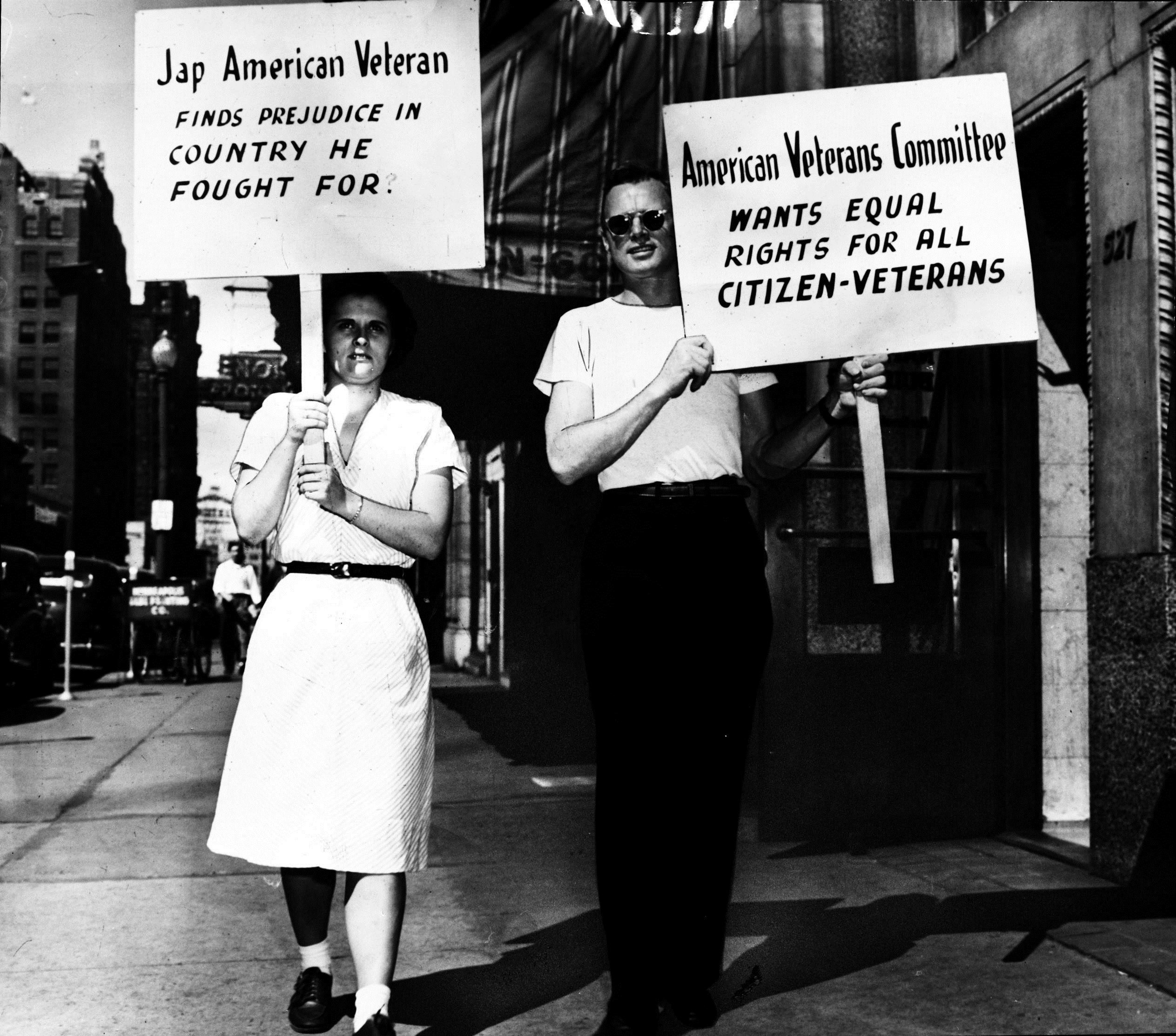

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, the Minneapolis Police Department quickly took on the role of controlling public opinion in Minneapolis. Working with J. Edgar Hoover and his recently formed Federal Bureau of Investigation, MPD established the Internal Security Division to gather intelligence on the people of Minneapolis. The ISD’s duties included investigating people who might be subversive, confiscating contraband equipment, and resettling Japanese and German nationals who were paroled from internment camps. At one point, anti-immigrant sentiments led to MPD regularly “checking on” over 10,000 “enemy aliens”.28Michael Fossum, History of the Minneapolis Police Department, (Minneapolis, Minn.: s.n., 1996), 5. The fears that led to this political witch hunt were completely unfounded – “enemy aliens” living in the United States didn’t take a single life throughout the whole war.

American Veterans Committee protest for Jon Matsuo, an American-Born veteran of Japanese descent. Matsuo was denied housing in a development specifically for WWII veterans as a result of racial discrimination.

The 1960s led to a host of changes in the department. From 1960 to 1965, MPD hired more than 150 new officers and civilian staff, increasing its total size to 809 employees.29Ibid., 7. They also created a number of new departments, including a narcotics unit and an early form of SWAT team known as the “Special Operations Division.”30Ibid., 20, 22. In 1966, they also established the school liaison program, known today as the School Resource Officer program, to “create a favorable rapport between the juvenile community and the police department.”31Ibid., 25-26. Of course, the school liaison program ignored the real problem – in many cases, students didn’t have a “favorable rapport” with the police because officers were brutal, unaccountable, and racist.

Tension between the Black community and the police was a constant in midcentury Minneapolis. Black people were systematically excluded from every part of the city except for the north side, denied access to well-paying jobs, blocked from homeownership, and routinely attacked by police officers. The Black community’s frustration with white supremacy came to a head in two riots on Plymouth Avenue: a smaller one in August 1966, and a larger one in July 1967.32Camille Venee, “‘The Way Opportunities Unlimited, Inc.’: A Movement for Black Equality in Minneapolis, MN 1966-1970” (Honors Thesis, Emory University, 2013, http://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/d6v0d). The first riot was in response to a number of factors including employment discrimination, but the later uprising had one particular cause: police racism.

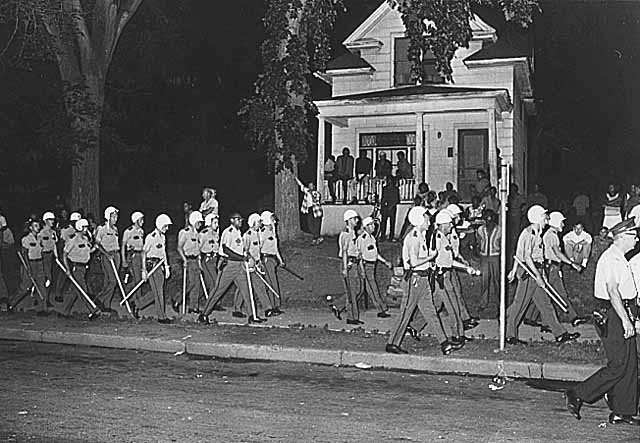

Police patrol North Minneapolis en masse Plymouth Avenue in the summer of 1967.

In four days in July 1967, police refused to intervene when buses wouldn’t bring Black people back to the north side following the Aquatennial parade, police allowed a white crowd to throw glass bottles at a Black crowd, police watched on as a group of four white boys savagely beat a Black boy, and police violently threw Black community members to the ground while breaking up a fight. The community was fed up, and on July 19th, 1967, the north side erupted into rioting. The uprising led to a massive police response and the deployment of the National Guard, with several community members arrested. (!)

In response to the riots, the mayor proposed a number of police reform initiatives, none of which solved the underlying problems in the department. What neither the mayor or the community could know was that the pattern established by the 1967 riot – police brutality leads to community outrage, leads to protests, leads to promises of reform, leads to a lack of meaningful change – would become a constant feature of policing in Minneapolis for the next fifty years.

Unreformable: MPD, 1967 – 2017

As the 1960s came to a close, demands for police accountability grew louder, and city officials proposed a set of reforms in response. One reform MPD implemented was the “Community Relations Division,” a public relations effort to improve the department’s image in communities of color through outreach.33Michael Fossum, History of the Minneapolis Police Department, (Minneapolis, Minn.: s.n., 1996). 7.

Another reform discussion centered around investigating police misconduct. Prior to the late 1960s, there was no formal process for investigating complaints against police officers, and the city scrambled to put one together. In the last few years of the decade, MPD created the Internal Affairs Unit to conduct internal investigations, and the City Council created a Civil Rights Commission with the authority to investigate civilian complaints about police officers. Both would become notorious for their inability to hold police accountable for brutality and misconduct. (!)

Not everyone had faith that the city’s reforms would bear fruit. In 1968, community patrols emerged in Black and Native communities to keep people safe, deescalate conflict, and prevent police violence. These programs were enormously successful, and their legacies continue today. (!)

The Minneapolis Police Department continued its charm offensive into the 1970s, instituting more “community policing” initiatives based on the idea that relationships between communities and the police were bad not because of police misconduct, but because of miscommunication. The programs included the “Model Cities” initiative, which encouraged officers to get out of their cars and talk with residents, and the Police Resource Team for Education, an effort to get cops into classrooms to talk with students about their work.34 Michael Fossum, History of the Minneapolis Police Department, (Minneapolis, Minn.: s.n., 1996). 8.35Minneapolis Police Department. 1872 – 1973: 101 Years of Service. 1973. Pg. 26

Meanwhile cops were working to undermine the reforms of the late 1960s. In 1971, Mayor Charles Stenvig, who had previously served as head of the police union, revoked the Civil Rights Commission’s authority to investigate complaints against police officers, once again making MPD the only local agency authorized to investigate MPD.36The Police Civilian Review Working Committee, A Model for Civilian Review of Police Conduct in Minneapolis: a report to the Mayor and City Council (Minneapolis, MN, 1989).

Without real accountability, “police-community relations” efforts did little to repair the relationship between MPD and communities of color. In 1974, the Minnesota Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that MPD was enforcing laws unfairly in the Native community, and in 1975, eleven incidents of police brutality led the Minnesota Department of Human Rights to begin an investigation of the Minneapolis Police Department, eventually finding that MPD’s recruitment and hiring practices were deeply racist. In response to the accusations, the department once again instituted surface level reforms in their recruitment and training practices, reforms that failed to fix the culture of the department. (!)

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, MPD had a reputation for being one of the most homophobic police departments in the country. MPD harassed queer people, enforced sodomy laws against them, failed to protect them from homophobic violence, and conducted raids on popular gay bathhouses.37Anthony V. Bouza, Police Unbound: Corruption, Abuse, and Heroism by the Boys in Blue, (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2001) Ebook locations 2734-2749. Though the last raid on a bathhouse occurred on February 10th, 1980, police harassment of queer folks remained frequent. In one 1982 example, cops showed up at the Saloon gay bar only to find a two homophobes attacking two gay men, who were fighting back. Rather than protecting the gay men, the cops arrested them and charged them with assault, disorderly conduct, and resisting arrest. (!)

The 1980s didn’t bring an improvement in the attitude of the Minneapolis Police Department – if anything, they made it worst. Upon being appointed police chief in 1980, Tony Bouza characterized the department as “damn brutal, a bunch of thumpers.”38“Drug Enforcement in Minority Communities: The Minneapolis Police Department,” Police Executive Research Forum/National Institute of Justice, 1994, p. 7. Bouza was hired as a police reformer, but even he later recognized that he had little effect on the culture of the department, describing himself as a “failed police executive” and writing in 2017 that he “did affect their actions…but changed nothing permanently – look around you.”39Tony Bouza,. “America’s Police Are Still Out Of Control,” Southside Pride (Minneapolis), August 21, 2017.

Michael Quinn was a Minneapolis police officer from 1975 to 1999, and has also spoken out about MPD’s departmental culture, telling stories of officers drinking on the job, committing burglary, savagely beating sex workers, and more. In each of those cases, the “code of silence” required that officers never report each other’s misconduct, and the officers involved went unpunished.40Michael Quinn, Walking with the Devil: the Police Code of Silence- the Promise of Peer Intervention, (S.l.: QUINN & ASSOCIATES, 2017) Ebook locations 64-67. Quinn faced his share of derision from officers for violating that code of silence, including threats from current police union head Bob Kroll.41Ibid. Ebook location 60. As Tony Bouza put it, “the Mafia never enforced its code of blood-sworn omerta with the ferocity, efficacy, and enthusiasm the police bring to the Blue Code of Silence.”42Anthony V. Bouza, Police Unbound: Corruption, Abuse, and Heroism by the Boys in Blue, (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2001) Ebook location 157.

By the end of the 1980s, the devastating wars on drugs and gang activity had led to increasingly militarized police departments being turned loose on communities of color. In 1989, this led to a number of tragedies at the hands of the Minneapolis Police Department: the brutal arrest of a group of Black youth at an Embassy Suites downtown, and the deaths of Black elders Lillian Weiss and Lloyd Smalley during a botched SWAT raid. (!) The incidents led to a number of protests demanding police accountability, which led to the creation of the Civilian Review Authority (CRA) in 1990. The CRA fared no better than its predecessor the Civil Rights Commission, and was ultimately ineffective in holding officers accountable. (!)

The newly established Civilian Review Authority wasn’t able to prevent a host of tragedies from happening throughout the 1990s as police continued to brutalize communities of color. In late 1990, police killed Tycel Nelson, a Black 17-year-old, while he was running away from them, provoking a new round of protests and demands for reform. (!) But the relationship between the police and the community was about to get even worse.

On September 25th, 1992, Metro Transit police beat an elderly Black man after he paid less than the full fare to ride a bus. Late that night, a group of youth, furious about the man’s treatment, ambushed and killed Minneapolis Police Officer Jerry Haaf. The police union took the opportunity to demand more money for drug enforcement and gang control, organizing rallies accusing the police chief, mayor, and city council of causing Haaf’s death by being soft on crime. Meanwhile, the Black community was being terrorized – the investigation into Haaf’s murder was swift and brutal, targeting many community members who had nothing to do with the shooting. (!)

The Black community wasn’t the only community of color being attacked by MPD in the early 90s – brutality against Native people was also frequent and horrifying. In one case, two passed out Native men were taken on a “rough ride” in a squad car’s trunk in 1993, (!) and in another case the same year, police officers working on a case at the Little Earth community shot a 16-year-old playing with a toy gun. (!) Another case at Little Earth in 1994 led to community outrage when two MPD officers kidnapped an East African man and tried to extort $300 from him. (!)

Misogyny was also a major problem in the Minneapolis Police Department. In September 1994, Officer Michael Ray Parent was charged with felony kidnapping and third-degree sexual assault for forcing a woman to perform oral sex on him to avoid a traffic ticket. Parent was eventually convicted in 1995, the first MPD officer to get sentenced to prison in over twenty years. (!)

In 1998, a group of protestors known as the Minnehaha Free State attempted to stop a proposed reroute of Highway 55 that would destroy a site sacred to the Dakota people. Their camp was raided by more than 800 officers, many of them from the Minneapolis Police Department. At the time, it was the largest law enforcement action in state history. (!)

The next year, Minnesota State Representative Rich Stanek led an effort to repeal residency requirements for police officers and other public employees around the state. The bill passed, making it illegal for local governments to require that police officers live in the city limits.43Rich Stanek, “Stanek Residency Freedom Bill becomes Law,” Representative Rich Stanek Press Release. Accessed March 15, 1999. http://www.house.leg.state.mn.us/GOP/goppress/Stanek/0309rsresidency.htm. That law is still in force in 2017, and Representative Stanek has since become Hennepin County Sheriff Stanek.

In 2003, another round of community protests erupted after 11 year old Julius Powell was hit by a wayward police bullet on the north side. (!) Community members asked the federal Department of Justice (DOJ) to intervene, and a mediator was sent to Minneapolis to try and resolve the conflict between the community and the police. The DOJ helped to broker a landmark agreement between community members and the police, creating a group called the Police Community Relations Council (PCRC) to try and improve police-community rapport. In addition to creating the PCRC, the agreement also required that the police chief institute over a hundred reforms in the department. The PCRC was gradually undermined by the city and forced to disband against their will in 2008. At the time of the PCRC’s dissolution, more than forty of the promised reforms remained incomplete. (!)

Even while the PCRC was active, there were a number of horrifying incidents of racism by MPD against Minneapolis residents. In 2006, MPD officers beat a Native-Latino man and locked him in a swelteringly hot squad car for more than half an hour. (!) Less than two months later, Minneapolis police officers shot and killed 19-year-old Fong Lee after chasing him down outside of a school. The officers maintained that Lee had been carrying a gun and posed a threat to officers, but evidence suggested that the gun was actually planted by MPD officers. (!)

2007 proved that even some police knew the department had serious problems with racism: that year, five Black police officers, including current MPD Chief Medaria Arradondo, sued the department for racial discrimination, demanding departmental reforms and hundreds of thousands of dollars. The city ended up settling the lawsuit for $2 million – and no reform requirements. (!)

In December 2007, the police department showed their reckless disregard for the lives of north side residents again when officers mistakenly executed a “no knock” raid on the house of an innocent Hmong family. Three police officers were nearly killed when the father shot them with a shotgun, assuming they were burglars. Luckily, no one was seriously injured. (!)

Another major scandal around police conduct came to light in 2009 when it was revealed that an interdepartmental unit called the Metro Gang Strike Force had been surveilling, brutalizing, and stealing from people of color in Minneapolis. The unit was disbanded in the chaos, but none of the officers involved, many of whom worked for MPD, were held accountable for their crimes. (!)

The 2010s brought new tragedies: unarmed 28-year-old David Smith was killed by police in September 2010 while having a troubling mental health episode. (!) In November 2010, Jason Yang was found dead under suspicious circumstances following a chase with police officers. (!). In 2011, MPD officers helped convict Cece McDonald of manslaughter after she was attacked by a transphobic white supremacist and killed him in self defense. (!)

With incidents of brutality a near constant in Minneapolis, the police union decided there was only one thing to be done: destroy the Civilian Review Authority. In 2012, they went to the state legislature and lobbied successfully for the passage of a bill prohibiting Civilian Review Boards from issuing statements on whether officers had committed misconduct, effectively taking away the limited power they had. In response, the City Council moved to create the Office of Police Conduct Review (OPCR), an equally ineffective police review agency based in the city’s Civil Rights Department. (!)

In 2013, the Minneapolis Police Department killed two people in one afternoon: Terrence Franklin was cornered and shot to death in a South Minneapolis basement, and Ivan Romero was killed less than an hour later when a squad car ran a red light and hit his motorcycle. (!)

Former Minneapolis police chief Janee Harteau and Minneapolis bike cops. Harteau says bike patrols are a good way for officers to be visible and accessible to citizens. Photo courtesy of Brandt Williams from MPR News

Meanwhile, MPD was undergoing a public relations makeover: Mayor Betsy Hodges and Police Chief Janee Harteau created yet another civilian oversight group, the Police Conduct Oversight Commission (PCOC), and instituted a program called MPD 2.0 calling for officers to treat community members exactly like they would treat members of their family.44Minneapolis Police Department, MPD 2.0: A New Policing Model (Minneapolis, MN, 2015). Like so many before them, these reforms did little to transform the department: the PCOC’s recommendations are largely ignored to this day. (!)

2014 saw one of the strangest moments in the history of the department. That year, Mayor Hodges was pushing for body cameras on officers as a solution to police misconduct, a plan that the police union hated. In an attempt to discredit her politically, they fed a story to local news station KSTP that she had been caught throwing gang signs in a photo with a community activist. In reality, the photo just showed the two pointing at each other. The story went viral, and millions around the country got a good laugh out of the absurdity of the claims. But once again, the police union had reminded an elected official of their considerable political power. (!)

In 2015, Minneapolis police officers shot and killed Jamar Clark, an unarmed Black man, while responding to a 911 call in north Minneapolis. In response, hundreds of community members occupied Plymouth Avenue outside the Fourth Precinct for 18 days, demanding the release of video footage of the incident and the prosecution of the officers involved. (!) Massive mobilizations against police racism continued into 2016 when Philando Castile was murdered by the Falcon Heights Police Department, prompting an occupation of the street outside the Governor’s Mansion.

MPD’s legacy of corruption, brutality, and murder continues in 2017. Earlier this year, a Minneapolis Police Officer shot and killed Justine Damond, an unarmed Australian woman, after she called 911 to report noises outside her home. The officers were wearing body cameras, but the cameras hadn’t been activated, and so the only accounts of the shooting were those of the police officers. (!) Mayor Hodges demanded the resignation of Police Chief Harteau following the shooting, promoting Medaria Arradondo to become the first Black police chief in the department’s history.

But the history of policing in Minneapolis and across the country has taught us that it doesn’t matter who the chief is, or even who runs the city: the police can’t be controlled. The Minneapolis Police Department was built on violence, corruption, and white supremacy. Every attempt ever made to reform it or hold it accountable has been soundly defeated. The culture of silence and complicity in the department, along with the formidable political power wielded by the police union, will continue to preserve the status quo as long as we keep placing our faith in the reforms that have failed us for the last 150 years. It’s time for us to face the reality – if we want to build a city where every community can thrive, it will have to be a city without the Minneapolis Police Department.

Click here to read an analysis of various failed reforms that have been suggested or implemented