1900

A Dollar A Day Keeps The Doctor Away: Turn-of-The-Century Corruption in MPD

1922

A Day To Remember: Police Brutality on June 20th, 1922

1934

‘Deputies Run’: The 1934 Teamsters Strike

1963

IAU, CRA, OPCR: Police (Un)accountability in Minneapolis

1967

The Fire Last Time: Plymouth Avenue

1968

Community Patrols in Minneapolis

1974

MPD Under Scrutiny

1982

Homophobic Cops: Attacks on Minneapolis’ Queer Community

1989

Raid Gone Wrong: The Deaths of Lillian Weiss and Lloyd Smalley

1990

The Murder of Tycel Nelson

1993

Rough Rides: Brutality Against Native Men

1993

‘Clean’ Records: A Shooting at Little Earth

1994

A Kidnapping at Little Earth

1994

Rapist With a Badge

1998

The Destruction of the Minnehaha Free State

2003

Trust as a Four Letter Word: The PCRC and the PCOC

2004

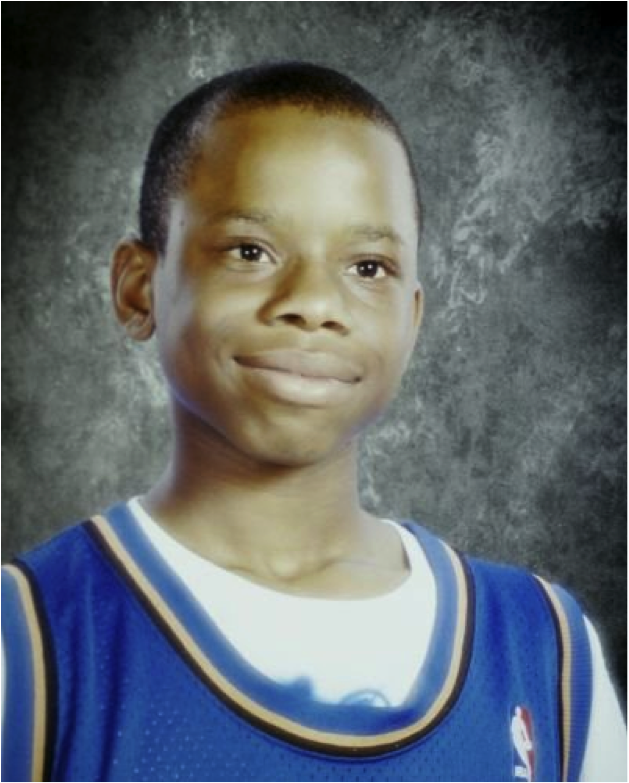

The Murder of Courtney Williams

2006

City Heat: The Mistreatment of Juan Vasquez

2006

The Murder of Fong Lee

2007

Cops Who Think Cops Are Racist – The Mill City 5

2007

Knock on Wood: A Botched Raid in North Minneapolis

2009

The Metro Gang Strike Force: Honor Among Thieves

2010

The Killing Of David Smith

2010

Jason Yang Dead After Encounter with Police

2011

Blaming (and Criminalizing) the Victim

2013

The Deaths of Terrance Franklin and Ivan Romero

2014

#Pointergate

2015

Justice for Jamar

2017

The Murder of Justine Damond

A Dollar A Day Keeps The Doctor Away: Turn-of-The-Century Corruption in MPD

“Burglaries were common. How many the police planned may never be known.”

– Lincoln Steffens, 1903 1Steffens, Lincoln. “The Shame of Minneapolis: The Ruin and Redemption of a City that was Sold Out.” McClure’s Magazine, January 1903

In his fourth term as Mayor of Minneapolis, Albert Alonzo “Doc” Ames (seen here c. 1890) appointed his brother as chief of police and ushered in an era of corruption in the city.

Police departments have a long and storied history of corruption. In many cities around the country, early police departments were part and parcel of the political machine: when a candidate won election, they would appoint their friends and supporters to cushy police jobs and, in turn, cops would use their unique position to help their benefactors stay in power.2Williams, Kristian. O ur Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America (2015). Chapter 2. Minneapolis was no exception to this; in 1903, thanks to an article written by journalist Lincoln Steffens, the Minneapolis Police Department briefly became the national poster child for bribery, graft, and extortion.

The Minneapolis Police Department briefly became the national poster child for bribery, graft, and extortion.Three years earlier, in 1900, Albert Alonzo “Doc” Ames had been elected to his fourth term as Mayor of Minneapolis. Ames was a physician and surgeon widely known in the community, and had seized upon that opportunity to get elected to office as both a Republican and a Democrat. In his first three terms as Mayor the doctor had been relatively restrained, but knowing this would likely be his last term in office, he “set out upon a career of corruption which for deliberateness, invention and avarice has never been equaled.” 3“The Shame of Minneapolis.” Penny. A Peterson, Minneapolis Madams: The Lost History of Prostitution on the Riverfront (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 129.

It all started with his cabinet: Doc Ames appointed his own brother, Fred Ames, to head the Minneapolis Police Department, and staffed it with friends and supporters who had no qualms about using the department for their own enrichment. Of 225 police officers, they immediately fired 107 of the most honest, and charged the remaining officers for the privilege of keeping their jobs. 4“The Shame of Minneapolis.” Penny. A Peterson, Minneapolis Madams: The Lost History of Prostitution on the Riverfront (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 129. Filling the jobs was easy: anyone who could pay an admission fee was welcomed onto the force. It was a good investment: under Ames, bribery and extortion were commonplace, and there was a lot of money to be made from policing.

The Minneapolis Police Department patrols with its head missing. The caption reads ‘But He Seems To Be Better Off Without It’. 1902 Cartoon from Hennepin County Library

Gambling houses, illegal bars, and opium dens came directly under police supervision; cops demanded a cut of the profits, and in many cases worked openly with organized crime. Some of the biggest victims were sex workers: they were “fined” monthly for their operations and forced to give “presents of money, jewelry, and gold stars to police officers.” 5“The Shame of Minneapolis.” Penny. A Peterson, Minneapolis Madams: The Lost History of Prostitution on the Riverfront (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 129.

Ames also required that brothels submit regularly to visits by physicians he appointed; these physicians charged huge amounts for their services and stopped by as often as they wanted. The corruption even escalated to outright theft; two MPD officers, Charles F. Brackett and Fred Malone, pulled off a string of successful robberies, including a burglary of the Pabst Blue Ribbon company offices, and were never held accountable. 6“The Shame of Minneapolis.”.; Penny. A Peterson, Minneapolis Madams: The Lost History of Prostitution on the Riverfront (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 129.

The Hennepin County Sheriff, the Hennepin County Prosecutor, and the Governor all proved unwilling or unable to hold Ames accountable. In the end, the only person who was able to stop him was Hovey C. Clarke, a businessman who was appointed the foreman of the Hennepin County Grand Jury. Clarke led the Grand Jury in a self-financed crusade against the mayor’s administration, indicting most of the city government, including Police Chief Ames, who was sentenced to six and a half years in prison in 1902. 7“The Shame of Minneapolis.” Penny. A Peterson,Minneapolis Madams: The Lost History of Prostitution on the Riverfront (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 129.

Doc Ames died in 1911, but the simple lesson he taught us remains: power corrupts.

Unsurprisingly given that he controlled the police department, Fred Ames was able to skip town without much trouble. He returned later and assumed control of MPD once more, but was eventually forced to resign and serve his prison sentence. Doc Ames also fled town, and was eventually caught and convicted of bribery. But the Supreme Court ended up overturning his conviction, and he returned to medical practice in Minneapolis. He died in 1911, but the simple lesson he taught us remains: power corrupts.

1. Steffens, Lincoln. “The Shame of Minneapolis: The Ruin and Redemption of a City that was Sold Out.” McClure’s Magazine, January 1903.

2. Williams, Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America (2015). Chapter 2.

3. “The Shame of Minneapolis.”.; Penny. A Peterson, Minneapolis Madams: The Lost History of Prostitution on the Riverfront (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 129.

4. “The Shame of Minneapolis.”

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

A Day To Remember: Police Brutality on June 20th, 1922

“A negro can get justice in the courts of this city, but many of them suffer severe cruelties before they reach them”

– The Minnesota Messenger, 19221“Negroes Protest Against Police Atrocities In This City,”The Minnesota Messenger, June 23rd, 1922.

Minneapolis was a dangerous place to be Black in the early 20th century. With a viciously racist streak demonstrated by its warm embrace of several Klu Klux Klan chapters, it’s no wonder that by the end of the 1920s, Black residents made up less than one percent of the population.2Delegard, Kirsten. “”A demand for justice and law enforcement”: a history of police and the near North Side -.” The Historyapolis Project. November 20, 2015. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://historyapolis.com/blog/2015/11/20/a-demand-for-justice-and-law-enforcement-a-history-of-police-and-the-near-north-side/. Those that did become residents faced any number of dangers in the city, including a racist police force more than happy to attack “undesirables”. This was exceptionally obvious on June 20th, 1922.

The cops returned an hour later, breaking up another crowd and ordering all Black clubs closed for several days in order to “prevent further trouble.”

An advertisement for the Klu Klux Klan featured in a local Minneapolis paper published mid 1922.

In the early hours of that morning, Minneapolis Police Officer Fitzpatrick, having heard about some Black men inviting white girls to a dance, decided to sweep the streets on the North side. Several men were standing outside the Elk’s Hall, waiting to get take-out meals, when Officer Fitzpatrick demanded that they move on. According to onlookers, Fitzpatrick was visibly drunk.3Delegard, Kirsten. “”A demand for justice and law enforcement”: a history of police and the near North Side -.” The Historyapolis Project. November 20, 2015. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://historyapolis.com/blog/2015/11/20/a-demand-for-justice-and-law-enforcement-a-history-of-police-and-the-near-north-side/. When they refused to move on, Fitzpatrick attacked them, beating several badly and arresting four on charges of disorderly conduct, tossing them into a paddy wagon.4“Crowd of 500 see cop get worst of struggle for gun,”Northwestern Bulletin, June 24th, 1922. The cops returned an hour later, breaking up another crowd and ordering all Black clubs closed for several days in order to “prevent further trouble.” 5“Crowd of 500 see cop get worst of struggle for gun,”Northwestern Bulletin, June 24th, 1922. Of course, it wasn’t clubs causing trouble, but police officers, and they weren’t done yet.

That night, Minneapolis Officer McNamee approached two young Black men in Mill City and demanded that they move on. When they refused, he hit a man with his club. When the man demanded that he stop, McNamee grabbed him and pulled out his revolver. He fired four shots, but the Black man managed to wrestle the gun away from the officer, and demanded he get on the ground. Choosing not to shoot the officer, the man ran off into the night, escaping despite multiple gun squads who were called in as backup.6“Citizens blame patrolman for Negro shooting,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, June 24th, 1922.

Luckily, a multiracial group of witnesses came forward, writing a public letter to the Morning Tribune explaining exactly what happened and placing all blame for the incident on the police.The Minneapolis Police Department tried to spin the story quickly; the next morning, reports appeared in the Minneapolis Morning Tribune that McNamee had been trying to arrest the man for disorderly conduct as a result of complaints that he had been seen speaking to white girls. 7“Citizens blame patrolman for Negro shooting,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, June 24th, 1922. Luckily, a multiracial group of witnesses came forward, writing a public letter to the Morning Tribune explaining exactly what happened and placing all blame for the incident on the police.

Leaders in the Black community, outraged at the events of the last day, called for a protest meeting to be held five days later, on June 25th.8“Negroes Protest Against Police Atrocities In This City,”The Minnesota Messenger, June 23rd, 1922 The meeting, facilitated by the Minneapolis chapter of the NAACP, resulted in a resolution demanding the officers be charged for their conduct and seeking an increase of the number of Black women on the police force.9Delegard, Kirsten. “”A demand for justice and law enforcement”: a history of police and the near North Side -.” The Historyapolis Project. November 20, 2015. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://historyapolis.com/blog/2015/11/20/a-demand-for-justice-and-law-enforcement-a-history-of-police-and-the-near-north-side/. Ultimately, these calls did little to effect change in the Minneapolis Police Department, and the next hundred years would be filled with dozens more calls for police accountability.

1. “Negroes Protest Against Police Atrocities In This City,”The Minnesota Messenger, June 23rd, 1922.

2. Delegard, Kirsten. “”A demand for justice and law enforcement”: a history of police and the near North Side -.” The Historyapolis Project. November 20, 2015. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://historyapolis.com/blog/2015/11/20/a-demand-for-justice-and-law-enforcement-a-history-of-police-and-the-near-north-side/.

3. Ibid.

4. “Crowd of 500 see cop get worst of struggle for gun,”Northwestern Bulletin, June 24th, 1922.

5. Ibid.

6. “Citizens blame patrolman for Negro shooting,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, June 24th, 1922.

7. Ibid.

8. “Negroes Protest Against Police Atrocities In This City.”

9. Delegard, “‘A demand for justice and law enforcement.”

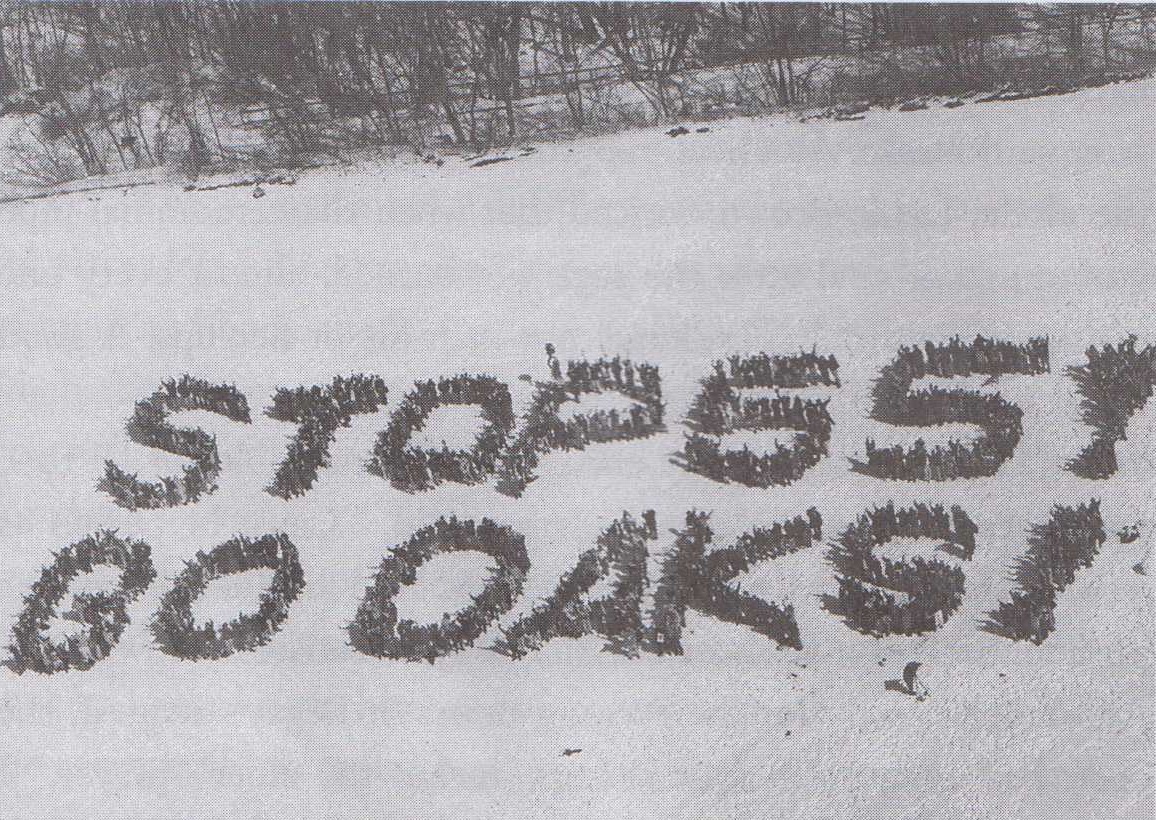

‘Deputies Run’: The 1934 Teamsters Strike

“Suddenly I knew, I understood deep in my bones and blood what Fascism was.”1Eric Sevareid, Not So Wild A Dream, 1946-Eric Sevareid, Noted WWII Reporter, on the aftermath of the 1934 “Battle Of Bloody Friday.”

The turn of the 20th century wasn’t a great time to be a worker in Minneapolis. Hours were long, wages were low, and any attempts at organizing into a union were quickly and brutally put down. The Citizens’ Alliance, a far-right group founded by prominent Minneapolis businessmen in 1903, used infiltration, intimidation, and violence to stop workers from organizing and prevent even reasonable labor reforms.2William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947(Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2003), xxvii. Two of their most powerful tools in doing this were the Minneapolis Police Department and the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office, both all too happy to help the rich and powerful maintain their hold on the city.

In 1917, the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office did something even more unbelievable: they gave the Citizens’ Alliance their own army.

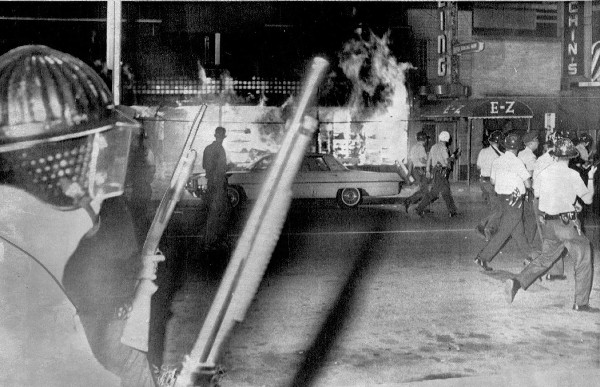

A photo of the escalating violence used against the Teamsters which lead to the “Battle of Bloody Friday,” in 1934 — sixty-seven strikers were shot, and two of them were killed at the behest of a police-led citizen militia.

Local law enforcement has a long history of violence against union members in Minneapolis. In 1889, MPD officers attacked a group of streetcar workers protesting a huge cut in their wages,3Cameron, Linda A. “Twin Cities Streetcar Strike, 1889.” MNopedia. February 8, 2016. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://www.mnopedia.org/event/twin-cities-streetcar-strike-1889. and in 1909, they protected strikebreakers during the machinists’ strike.4William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947(Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2003) 37 In 1917, the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office did something even more unbelievable: they gave the Citizens’ Alliance their own army.

The Civilian Auxiliary, organized by the Citizens’ Alliance during World War I in April 1917, was a group of local businessmen, most past the age of service, who practiced military drills as a way to better understand how to “back up the boys at the front.”5William Millikan, “The Minneapolis Civic and Commerce Association versus Labor during World War I,”Minnesota History Quarterly, Spring 1986. The true purpose of the Auxiliary became clear later that year when, hearing rumors of a possible strike by streetcar workers, the sheriff deputized every member of the Civilian Auxiliary, giving them the same authority to make arrests and use force that the sheriff himself had. When the strike began in October 1917, 600 CA men armed with rifles and clubs mobilized to protect the railways and quickly suppressed the strike.6Millikan, A Union Against Unions, 125-126 The Civilian Auxiliary was disbanded after the end of WWI, but the Citizens’ Alliance maintained close relations with the police chief and the sheriff, aware that there would always be a need for legal violence against strikers. That relationship would prove particularly useful during what was at the time the largest labor mobilization in Minneapolis’ history: the 1934 Teamsters Strike.

On May 16th, 1934, thousands of truck drivers around the city went on strike as members of Teamsters Local 574, demanding recognition of their union, higher wages, and shorter working hours.7Teamsters. “1934 Minnesota Strike.” Accessed November 15, 2017. https://teamster.org/about/teamster-history/1934 They moved quickly to stop the flow of goods into the city, declaring that no transportation of goods would happen until their demands were met. On the third day of the strike, the Citizens’ Alliance, determined to halt the strike’s momentum, called a public meeting to assemble a force of strikebreakers. Over 700 men joined up – former cops, doctors, lawyers, clerks, salesmen, fraternity brothers, and even inmates from the county jail who were released to fight the strikers.8Sevareid, Not So Wild A Dream, 57. They were quickly sworn in as special officers of the Minneapolis Police Department or deputies of the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office, and armed with baseball bats, lead pipes, and other improvised weapons.9Millikan, A Union Against Unions, 273. This army, commanded by ex-military men hired for the job by the Citizens’ Alliance, prepared to go to battle against the Teamsters.

On May 22nd, 1934, tensions came to a head. Around noon, the police and their deputies tried to stop strikers from entering the labor headquarters. Instead a group of several thousand strikers forced the deputies back to Third Avenue and Sixth Street, and the confrontation turned into an all-out battle. Deputies and strikers alike were attacked with “hoses, lead pipes, baseball bats, and iron hooks”.10Millikan, A Union Against Unions, xxx But unlike the 1917 Civilian Auxiliary, the CA forces in 1934 were poorly trained and outnumbered, and the few sworn police officers nearby did nothing to intervene. In less than an hour, the strikers utterly crushed the deputies, killing two of them, and securing the streets. In light of the total victory of the union force, the skirmish was later dubbed the “Battle of Deputies Run”.11Blantz, “Father Haas and the Minneapolis Truckers’ Strike of 1934,”1970. Four days later, on May 25th, under pressure from the governor and the national guard, the Teamsters and the CA signed a truce.

But the major issues that had led to the strike were unresolved, and it became immediately clear that the peace would not last. Knowing this, Minneapolis Police Chief Johannes asked the city council for 400 more police officers and a police school, so that the officers could “be trained just like an army to handle riots”.12Millikan, A Union Against Unions,277. His expanded budget request also included $1000 for machine guns and money to buy 800 rifles.13Millikan, A Union Against Unions,277. The Minneapolis Police Department wouldn’t be caught unawares by truck drivers again; when the strike resumed on July 16th, they were ready for war.

On July 20th, a non-union delivery truck escorted by twenty-five squad cars made a delivery to the Slogum-Bergren company in the market district. When the truck attempted to leave, a union truck pulled in front of it, cutting it off and surrounding it with picketers. It was then that the Minneapolis police sprung their trap, jumping out of their squad cars with shotguns and shooting to kill. In what would come to be called the “Battle of Bloody Friday,” sixty-seven strikers were shot, and two of them, John Belor and Henry Ness, were killed.14Millikan, A Union Against Unions, 280

In the aftermath of the shooting, the police reported that they had been “fighting for their lives,” a claim that lost credibility when it was revealed that the vast majority of gunshot wounds were on strikers’ backs – they’d been shot as they were running away.

Police and Strikers in Tear Gas Cloud during the 1934 Teamsters Strike.

A National Guard squad appeared within minutes, putting a temporary halt to the fighting. In the aftermath of the shooting, the police reported that they had been “fighting for their lives,”15Sevareid, Not So Wild A Dream, 58. a claim that lost credibility when it was revealed that the vast majority of gunshot wounds were on strikers’ backs – they’d been shot as they were running away.16Blantz, “Father Haas and the Minneapolis Truckers’ Strike of 1934,”279. Commenting on the shooting, CA Secretary Schroeder noted that “if the troops had not come in and interfered, the strike would have been soon over. Because there are very few men who stand up in a strike when it’s a question of they themselves getting hurt and killed”.17Thomas E. Blantz, “Father Haas and the Minneapolis Truckers’ Strike of 1934,”Minnesota History (Spring 1970), 280.

The night of the shooting, union leaders organized a march on City Hall. At least one man wasn’t there: Eric Sevareid, who would become one of the most famous WWII reporters, then a rookie reporter covering the strike for the Minneapolis Star. In his memoir, he recalls visiting the strikers in the hospital that night, a passage worth including in its entirety:

“...the nurses at the city hospital that night demonstrated to me that nearly all the injured strikers had wounds in the backs of their heads, arms, legs, and shoulders: They had been shot while trying to run out of the ambush. Suddenly I knew, I understood deep in my bones and blood what Fascism was. I had learned the lesson in such a way that I could never forget it, and I had learned it in the precise area which is psychologically the most removed from the troubles of Europe—in the heart of the Middle West. I went home, as close to becoming a practicing revolutionary as one of my noncombative instincts could ever get.”- Eric Sevareid, Not So Wild A Dream, 58.

In the end, not even shooting the Teamsters with shotguns could stop them from organizing: the strike continued for nearly another month, with the Citizens’ Alliance, the Teamsters, and the National Guard all fighting for control of the city. Eventually, the will of the Citizens’ Alliance collapsed, and on August 21st, they signed a federally mediated agreement with the Teamsters.18Millikan, A Union Against Unions, 287. “VICTORY” read the headline in a local labor newspaper – the union leaders hadn’t gotten everything they wanted, but they were allowed to hold union elections and quickly set about organizing the trucking agency.

Though the Citizens’ Alliance didn’t disappear overnight, their influence waned after 1934. Unions had won a previously impossible victory in Minneapolis, and more were waiting to be achieved. By WWII, the CA’s anti-union policies had fallen out of favor, and it ceased to become a political power.19Lois Quam and Peter Rachleff, “Keeping Minneapolis an open shop town: the Citizen’s Alliance in the 1930s,”Minnesota History (Fall 1986), 105-117

The masters may have fallen out of favor, but their tools remain. In the eighty-three years since the Teamsters’ Strike ended, the Minneapolis Police Department and the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office have refined and perfected their crowd control tactics, viciously attacking protestors and community members who advocate for social justice from the Fourth Precinct to the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. But if even the powerful Citizens’ Alliance can be defeated, perhaps we can look forward to a day where social justice advocates don’t have to fear for their lives while trying to build a better world.

1. Eric Sevareid, Not So Wild A Dream, 1946.

2. William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947(Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2003), xxvii.

3. Cameron, Linda A. “Twin Cities Streetcar Strike, 1889.” MNopedia. February 8, 2016. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://www.mnopedia.org/event/twin-cities-streetcar-strike-1889.

4. Millikan, A Union Against Unions, 37.

5. William Millikan, “The Minneapolis Civic and Commerce Association versus Labor during World War I,”Minnesota History Quarterly, Spring1986.

6. Millikan, A Union Against Unions, 125-126.

7. Teamsters. “1934 Minnesota Strike.” Accessed November 15, 2017. https://teamster.org/about/teamster-history/1934.

8. Sevareid, Not So Wild A Dream, 57.

9. Millikan, A Union Against Unions, 273.

10. Ibid, xxx.

11. Blantz, “Father Haas and the Minneapolis Truckers’ Strike of 1934,”1970.

12. Millikan, A Union Against Unions,277.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid, 280.

15. Sevareid, Not So Wild A Dream, 58.

16. Blantz, “Father Haas and the Minneapolis Truckers’ Strike of 1934,”279.

17. Thomas E. Blantz, “Father Haas and the Minneapolis Truckers’ Strike of 1934,”Minnesota History (Spring 1970), 280.

18. Millikan, A Union Against Unions, 287.

19. Lois Quam and Peter Rachleff, “Keeping Minneapolis an open shop town: the Citizen’s Alliance in the 1930s,”Minnesota History (Fall 1986), 105-117.

IAU, CRA, OPCR: Police (Un)accountability in Minneapolis

“It is a waste of time for anyone to file a complaint against the police.” 1Furst, Randy. “New Law throws Minneapolis police oversight in turmoil.” Star Tribune, April 6, 2012. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://www.startribune.com/new-law-throws-minneapolis-police-oversight-in-turmoil/146497655/ – Kenneth Brown, former chairman of the Minneapolis Civil Rights Commission, 2012

When police brutality becomes particularly obvious in Minneapolis, community members often call for increased police accountability. The idea is that with the oversight of civilian review boards, internal affairs units, or other administrative bodies, Minneapolis police officers will stay true to their motto, “to protect with courage and to serve with compassion.” Unfortunately, this is almost never the case. From the beginning of MPD’s existence in 1887 to the present day, accountability mechanisms have been nearly useless at preventing police misconduct and brutality.

Despite the brutality of MPD in the late 19th and early 20th century towards people of color, the urban poor, and labor organizers, there was no real investigation of civilian complaints against the department until 1963. Until then, the only way to address police brutality was to report it directly to Department management, who was then free to dismiss it without ever making any record of the complaint.

Police arresting a man who was homeless in Minneapolis during the early 1960s.

In 1963, a Civil Rights investigation found that “minority group members generally [lacked] faith that their complaints would dealt with properly,”2Minnesota State Advisory Committee. Report on police-community relations in Minneapolis and St.Paul. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. (1965). 6. and recommended the creation of an “impartial police review program with full citizen participation,” a recommendation that was mostly ignored by the city- Minneapolis’ first Civilian Review Board was created in 1963, but it lacked any official status, and ceased to exist after a lawyer found that its members could be sued for defamation.3 Police Civilian Review Working Committee. A Model For Civilian Review of Police Conduct in Minneapolis.1989. For most of the 1960s, there continued to be no group investigating police misconduct complaints.

In the late 1960s The Minneapolis Police Department created the Internal Investigation Unit (now the Internal Affairs Unit, or IAU) to investigate complaints against its own officers, a system widely criticized as ineffective to this day. As a city report put it decades later, “the Internal Affairs Unit has a history of not investigating or thoroughly investigating citizen complaints…officers could not be expected to thoroughly investigate other officers with whom they must later serve.”4Police Civilian Review Working Committee. A Model For Civilian Review of Police Conduct in Minneapolis.1989, 32 Community members have similar complaints about the IAU today.

In 1967, the City Council, pressured by national and local civil rights organizations, established the Minneapolis Civil Rights Commission5 Originally the Human Rights Commission, then the Minneapolis Commission on Civil Rights to investigate civil rights complaints in Minneapolis.6Records of the Way, 1966 – 1972, Location 116.K.14.84 Box 8, Minnesota Historical Society. The Commission, staffed by civilians, was given the power to investigate complaints against police officers. Like the first Civilian Review Board, the Civil Rights Commission was largely ineffective; in 1969, after police violently broke up a protest, community organizations and a Star Tribune editorial called for even greater police oversight.7Police Civilian Review Working Committee. A Model For Civilian Review of Police Conduct in Minneapolis. 1989. 5. Those calls went unheeded.

Meanwhile, the Police Department and the Police Federation fought tooth-and-nail against the commission, refusing to turn over documents, answer questions, or provide testimony in hearings.8Ibid.; Records of the Way, 1966 – 1972, Location 116.K.14.84 Box 8, Minnesota Historical Society. Eventually, they won: in 1969, the head of the police union, Charles Stenvig, was elected mayor, and in 1971, the Civil Rights Commission’s power to investigate police misconduct was revoked by the city.9Police Civilian Review Working Committee. A Model For Civilian Review of Police Conduct in Minneapolis. 1989. 6. For the next two decades, the only agency empowered to investigate police misconduct would be the police department itself.

Out of 81 complaints of excessive use of force, the IAU didn’t find one example of wrongdoing.The Internal Affairs Unit continued to be incredibly ineffective at holding officers accountable through the late 1980s; for example, under the last year of Tony Bouza’s tenure as Minneapolis Chief in 1988, 83.6% of the 231 complaints reviewed by the department’s internal affairs unit were dismissed with no action whatsoever. Out of 81 complaints of excessive use of force, the IAU didn’t find one example of wrongdoing.10Brunswick, Mark. “Watching the police is tough job for everyone.” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), January 29, 1990.

By the end of the 1980s, the killing of Lloyd Smalley and Lillian Weiss, along with the brutal arrests of a number of Black youth in an Embassy Suites downtown, led to renewed calls for civilian oversight. In September 1990, a working committee convened by the city recommended the creation of a new oversight group, one that the police would be required to cooperate with. As always, police fought the proposal tooth-and-nail; the Police Federation argued that civilian review would take away officers’ right to due process11Hotakainen, Rob. “Council panel votes for civilian review of police.” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), January 18, 1990., and the department’s SWAT team threatened to stop working in protest.12Diaz, Kevin, and Jill Hodges. “Members of high-risk police unit threaten work stoppage in protest.” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), January 23, 1990. The City Council passed the proposal anyways, creating the Civilian Review Authority13Originally the Civilian Police Review Authority, which had the ability to investigate complaints and issue “findings of fact,” but left disciplinary action up to the police chief. Unsurprisingly, the Civilian Review Authority also failed to hold police accountable. From 1991 to 1996, the CRA resolved 826 complaints, more than 85% of which weren’t even fully investigated by the board. Even after investigation, only 6% of complaints were sustained.14Minneapolis Civilian Police Review Authority. Redesign Team Report. Minneapolis, MN, 1997. 7. Five years in, not one officer had ever been fired as a result of a CRA complaint.15Minneapolis Civilian Police Review Authority. Redesign Team Report. Minneapolis, MN, 1997. Exhibit H. By nearly all accounts, it never got better; even a police federation spokesperson once described the CRA as “dysfunctional.“16Furst, Randy. “New Law Throws Minneapolis Police Oversight Into Turmoil.” Star Tribune, April 6, 2012. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://www.startribune.com/new-law-throws-minneapolis-police-oversight-in-turmoil/146497655/ Problems with the CRA continued for the next two decades, into the 2010s.

In December 2011, the CRA board issued a public statement declaring that they had no confidence the police chief would impose discipline when they recommended it.17Furst, Randy. “New Law Throws Minneapolis Police Oversight Into Turmoil.” Star Tribune, April 6, 2012. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://www.startribune.com/new-law-throws-minneapolis-police-oversight-in-turmoil/146497655/. In response, the Minneapolis Police Federation, one of the most powerful lobbying groups in the state, pushed the state legislature to pass a law making it illegal for the Civilian Review Authority to issue “findings of fact.” It won overwhelming bipartisan support over vehement opposition of Minneapolis’ Mayor and City Council, and was signed into law by governor Mark Dayton in the spring of 2012. As Councilmember Cam Gordon said at the time, “I think this effectively forces us to re-evaluate the Civilian Review Authority.”18Furst, Randy. “New Law Throws Minneapolis Police Oversight Into Turmoil.” Star Tribune, April 6, 2012. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://www.startribune.com/new-law-throws-minneapolis-police-oversight-in-turmoil/146497655/.

It did. In the fall of 2012, the City Council dismantled the CRA, replacing it with a new oversight agency under the city’s Civil Rights Department: the Office of Police Conduct Review, or OPCR, consisting of two civilians and two police officers. The OPCR remains the city’s police oversight agency today. Predictably, it has many of the same issues as its predecessors, with the vast majority of cases being dismissed without any disciplinary action whatsoever. As of August 2017, 1,175 complaints have been filed with the OPCR since its inception, and only 36 have resulted in disciplinary actions other than coaching. In other words, the likelihood of discipline from a complaint is around 3%.19Office of Police Conduct Review. “Data Portal.” Accessed November 15, 2017. http://www.minneapolismn.gov/civilrights/policereview/archive/index.htm. And that’s only the complaints that are successfully filed. An August 2017 report from the Police Conduct Oversight Commission found that in 13 out of 15 attempts to test-file a complaint at Minneapolis police precincts, people were not given opportunities to file complaints, and information on how to file online was inconsistent.20Cox, Peter. “Issues abound in filing police misconduct complaints, report finds.” Minnesota Public Radio. August 9, 2016. Accessed November 15, 2017. https://www.mprnews.org/story/2016/08/09/issues-found-filing-minneapolis-police-misconduct-reports

It’s clear that the acorn doesn’t fall far from the oak tree. Since 1963, five separate bodies have been formed to reign in the Minneapolis Police Department. Every single one of these bodies has been weak, unhelpful, and ineffective. When any one of them managed to gain even limited power over police misconduct, the police federation worked successfully to limit their power and destroy them. Our history is clear: real police accountability, civilian review or otherwise, is impossible within our current system.

1. Furst, Randy. “New Law throws Minneapolis police oversight in turmoil.” Star Tribune, April 6, 2012. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://www.startribune.com/new-law-throws-minneapolis-police-oversight-in-turmoil/146497655/.

2. Minnesota State Advisory Committee. Report on police-community relations in Minneapolis and St.Paul. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. (1965). 6.

3. Police Civilian Review Working Committee. A Model For Civilian Review of Police Conduct in Minneapolis.1989.

4. Ibid, 32.

5. Originally the Human Rights Commission, then the Minneapolis Commission on Civil Rights

6. Records of the Way, 1966 – 1972, Location 116.K.14.84 Box 8, Minnesota Historical Society.

7. Police Civilian Review Working Committee. A Model For Civilian Review of Police Conduct in Minneapolis. 1989. 5.

8. Ibid.; Records of the Way, 1966 – 1972, Location 116.K.14.84 Box 8, Minnesota Historical Society.

9. Police Civilian Review Working Committee. A Model For Civilian Review of Police Conduct in Minneapolis. 1989. 6.

10. Brunswick, Mark. “Watching the police is tough job for everyone.” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), January 29, 1990.

11. Hotakainen, Rob. “Council panel votes for civilian review of police.” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), January 18, 1990.

12. Diaz, Kevin, and Jill Hodges. “Members of high-risk police unit threaten work stoppage in protest.” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), January 23, 1990.

13. Originally the Civilian Police Review Authority.

14. Minneapolis Civilian Police Review Authority. Redesign Team Report. Minneapolis, MN, 1997. 7.

15. Ibid. Exhibit H.

16. Furst, Randy. “New Law Throws Minneapolis Police Oversight Into Turmoil.” Star Tribune, April 6, 2012. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://www.startribune.com/new-law-throws-minneapolis-police-oversight-in-turmoil/146497655/.

17. Ibid. 18 Ibid. 19 Office of Police Conduct Review. “Data Portal.” Accessed November 15, 2017. http://www.minneapolismn.gov/civilrights/policereview/archive/index.htm.

18. Ibid.

19. Office of Police Conduct Review. “Data Portal.” Accessed November 15, 2017. http://www.minneapolismn.gov/civilrights/policereview/archive/index.htm.

20. Cox, Peter. “Issues abound in filing police misconduct complaints, report finds.” Minnesota Public Radio. August 9, 2016. Accessed November 15, 2017. https://www.mprnews.org/story/2016/08/09/issues-found-filing-minneapolis-police-misconduct-reports.

The Fire Last Time: Plymouth Avenue

“A fire of protest against indignity and denial is burning here as it is elsewhere. It will not be extinguished by promises or pledges that are not translated into action.”1Camille Venee Maddox, “‘The Way Opportunities Unlimited Inc.’: A Movement for Black Equality in Minneapolis, MN 1966-1970,” (Honors Thesis, African American Studies, Emory University 2013), 34.– Minneapolis Mayor Arthur Naftalin, 1963 inaugural speech

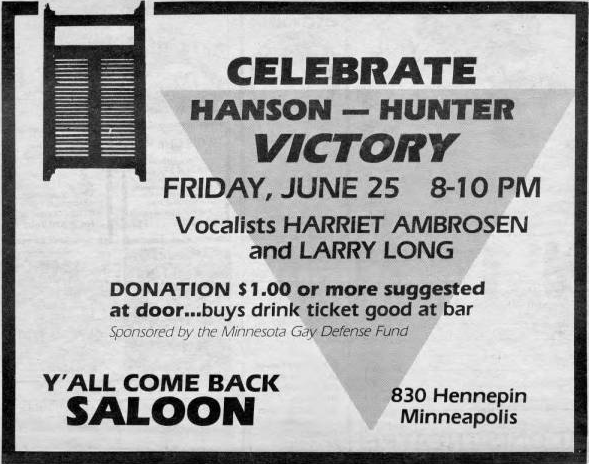

Taken July 21, 1967 —

Minneapolis police officers passed a blazing grocery store on Plymouth Avenue on the city’s North Side.

By the mid-1960s the Civil Rights movement was in full swing in Minneapolis, with Black residents on the North Side demanding jobs, decent housing, and an end to police violence. On July 15th, 1967, the evening of one of the Aquatennial parades in Minneapolis, things were particularly bad for Black community members. Bus drivers refused to let Black residents board buses back to North Minneapolis, forcing many residents to walk five or six miles back to their homes as white passerby threw bottles and other debris at them. Police officers stood by, refusing to intervene. The worst incident happened on Plymouth avenue in North Minneapolis, where four white boys beat a Black boy while police watched. When the Black boy asked for a ride to the hospital from the police, they replied only, “Nigger, go home; there is nothing wrong with you.”2Camille Venee Maddox, “‘The Way Opportunities Unlimited Inc.’: A Movement for Black Equality in Minneapolis, MN 1966-1970,” (Honors Thesis, African American Studies, Emory University 2013), 34. The mayor and city council refused to acknowledge police wrongdoing that night.

Things got even worse on July 19th. Minneapolis Police Department officers violently broke up a fight downtown, throwing a number of Black community members to the ground. Meanwhile, a bar owner, who had previously shot two black patrons and had not been held accountable by the police, shot another Black community member. In response, and in protest of systemic racism more broadly, Black community members, along with poor white and Native community residents, rose up and began setting fire to businesses that had previously discriminated against Black residents. Mayor Art Naftalin immediately dismissed the riots as “not related to deficiencies or neglect” and “simply a product of lawlessness,” in the Minneapolis Tribune and worked with the governor to call in the National Guard. 29 arrests were made.3Camille Venee Maddox, “‘The Way Opportunities Unlimited Inc.’: A Movement for Black Equality in Minneapolis, MN 1966-1970,” (Honors Thesis, African American Studies, Emory University 2013, 38; Records of the Way, 1966 – 1972, Location 116.K.14.84 Box 8, Minnesota Historical Society.

Despite his claims that the riots had nothing to do with deficiencies in Black communities, after the riot had ended Mayor Naftalin met with hundreds of community members, who made demands that would help Minneapolis end racial inequality once and for all. On July 28th, 1967, the mayor took many suggestions back to the city council, proposing a broadened civil rights ordinance, the creation of a cadet system for the police department, a renewed effort to hire minority police officers, and other reforms.4Mayor Naftalin Proposes Program Of Depth To Meet Community Problem,”Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder, August 3rd, 1967. But these proposals, ignoring the underlying issues that lead to the riot, ultimately failed to make a major difference on the North side. Fifty years later, many of the same conditions that led to the 1967 Riot are still a constant in Minneapolis.

1. Camille Venee Maddox, “‘The Way Opportunities Unlimited Inc.’: A Movement for Black Equality in Minneapolis, MN 1966-1970,” (Honors Thesis, African American Studies, Emory University 2013), 34.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid, 38; Records of the Way, 1966 – 1972, Location 116.K.14.84 Box 8, Minnesota Historical Society.

4. “Mayor Naftalin Proposes Program Of Depth To Meet Community Problem,”Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder, August 3rd, 1967.

Community Patrols in Minneapolis

The Soul Force

In the wake of the 1967 Riot on Plymouth Avenue, community leaders created many new institutions to fight back against the racism and police brutality that had prompted the protests. One of these programs was the “Black Patrol,” started by a group of community members that patrolled Black communities in much the same way that the Black Panthers were doing in Oakland.1Camille Venee Maddox, “‘The Way Opportunities Unlimited Inc.’: A Movement for Black Equality in Minneapolis, MN 1966-1970,” (Honors Thesis, African American Studies, Emory University 2013), 57. In partnership with “The Way,” an anti-racist community center, they also established the “Soul Force” in 1968, a patrol group dedicated to nonviolence and made up of volunteers of many racial backgrounds.2Ibid, 58.

The Soul Force and the Black Patrol worked together. Often, the Soul Force would be the first on the scene, and then would call the Black Patrol or Police for situations that required the use of force.3“The Soul Force: A Program of “The Way” Community Center”, Records of The Way, Inc., Minneapolis 1966-1974. Gale Family Library, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN. They had many successful interventions, including preventing a white man from leveling a shotgun at a crowd of Black people, and preventing community-police tension from erupting into a brawl at the Aquatennial parade.4Ibid. Another important effect the Soul Force had was on its white volunteers: many of them came to understand systemic racism while volunteering with the patrol. After seeing Minneapolis Police Department Officers break up a flag football game, one white volunteer remarked, “that to me illustrated how police treat Black people. Such a thing would never have happened in a white community.”5A. Karim Ahmed, “Side by Side On the North Side,” Davis, Records of The Way Inc. It wasn’t long before the Soul Force and the Black Patrol would be joined by another group: the AIM Patrol.

The AIM Patrol

A woman speaking to the crowd at an AIM Forum on police brutality, c. 1968. Photograph by Roger Woo, courtesy of the American Indian Movement Interpretative Center.

In July of 1968, a group of around 200 community members gathered on Plymouth Avenue to address the ongoing racism and violence experienced by the Native community in Minneapolis.6Wilson, Brianna. “AIM Patrol, Minneapolis.” MNopedia. Accessed December 28, 2016. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/aim-patrol-minneapolis. Though they didn’t know it yet, the group would eventually become known as the American Indian Movement, or AIM, a national movement of Native resistance. The meeting came in an environment of extreme levels of criminalization and incarceration of Natives – though they made up only ten percent of the city’s population, seventy percent of the Minneapolis jail population was Native, and three of AIM’s founders – Clyde Bellecourt, Eddie Benton-Benei, and Dennis Banks, had been incarcerated.7Birong, Christine. “The Influence of Police Brutality on the American Indian Movement’s Establishment in Minneapolis, 1968-69.” GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN INDIAN STUDIES. April 6, 2009. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://arizona.openrepository.com/arizona/bitstream/10150/193405/1/azu_etd_10464_sip1_m.pdf. p. 31.

So it’s probably unsurprising that when the community gathered that day, their number one priority was to fight police brutality – as Dennis Banks put it, “I’m tired of seeing the paddy wagon parking on Franklin at 9 o’clock and waiting to load up my people… The Negroes got rid of that sort of thing on Plymouth Av. with their patrol, and we’re going to have to do the same thing.”8Ibid, 48. Their solution was a militant cop watch group called the AIM Patrol.

The AIM Patrol was a network of volunteers who would patrol the Phillips neighborhood in Minneapolis, monitoring and documenting police activity while stepping into crises to de-escalate and resolve conflicts.9Ibid. 42. Patrol members wore red jackets and drove in red cars to identify themselves to neighbors and cops while on watch.

Their impact was dramatic: after 5 weeks of patrolling, AIM leaders announced that there had been no Native people arrested – a far cry from the five or six a day that had been arrested before the Patrol was established. After the first six months of patrolling, the percentage of the jail population that was Native had dropped from 70% to 10%.The Patrol worked: they were often quicker to respond to calls in Native communities than the Minneapolis Police Department, and sometimes MPD even called them for help.10Ibid. 51. Unfortunately, the cooperation didn’t last long: officers grew to resent the “interference” of the AIM Patrol, and often harassed their members, lurking outside the Patrol’s headquarters, beating activists, and even throwing members of the Patrol in the Mississippi River.11Ibid. 55.

The AIM Patrol’s first iteration disbanded around 1975, but its legacy remains – there have been multiple revivals of the Patrol in Minneapolis since the 1970s, most recently in 2010, and AIM activists remain a constant presence in the fight for Indigenous sovereignty.12Wilson, Brianna. “AIM Patrol, Minneapolis.” MNopedia. Accessed December 28, 2016. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/aim-patrol-minneapolis.

1.Camille Venee Maddox, “‘The Way Opportunities Unlimited Inc.’: A Movement for Black Equality in Minneapolis, MN 1966-1970,” (Honors Thesis, African American Studies, Emory University 2013), 57.

2.Ibid, 58.

3.“The Soul Force: A Program of “The Way” Community Center”, Records of The Way, Inc., Minneapolis 1966-1974. Gale Family Library, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN.

4.Ibid.

5.A. Karim Ahmed, “Side by Side On the North Side,” Davis, Records of The Way Inc.

6.Wilson, Brianna. “AIM Patrol, Minneapolis.” MNopedia. Accessed December 28, 2016. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/aim-patrol-minneapolis.

7.Birong, Christine. “The Influence of Police Brutality on the American Indian Movement’s Establishment in Minneapolis, 1968-69.” GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN INDIAN STUDIES. April 6, 2009. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://arizona.openrepository.com/arizona/bitstream/10150/193405/1/azu_etd_10464_sip1_m.pdf. p. 31.

8.Ibid, 48.

9.Ibid. 42.

10.Ibid. 51.

11.Ibid. 55.

12.Wilson, Brianna. “AIM Patrol, Minneapolis.” MNopedia. Accessed December 28, 2016. http://www.mnopedia.org/group/aim-patrol-minneapolis.

MPD Under Scrutiny

From 1974 to 1976, independent investigators found the Minneapolis Police Department’s treatment of minority groups and its hiring processes unacceptable. A 1974 study of the Twin Cities Native American Community, by the Minnesota Advisory Committee to the US Commission on Civil Rights, found an “unequal application” of the law in Indian and white communities, with minority persons frequently charged with public profanity, or breach of the peace, usually in reaction to insults and abuse from police. In June of 1975, 11 incidents of police brutality that occurred within a short time span in 1975 led to three public hearings held by the Minnesota State Department of Human Rights, in conjunction with the Urban League, NAACP and AIM. MPD wasn’t thrilled – Captain Wayne Hartley commented that “We are police officers not black or Indian or white–and it is prejudiced to talk otherwise.”1League of Women Voters of Minneapolis, The Police and the Community, a second look (Minneapolis: The League), 1976.

In 1975, The Minnesota Department of Human Rights issued a probable cause finding of discrimination in the hiring and recruitment of the Minneapolis Police Department. In response, the police department ended the use of a 200 question written screening test that contained math and vocabulary questions (found by the MDHR to be “not job related”). The rookie class in 1975 had 96 hours of Karate and 14 hours of Transactional Analysis added to their training, with the goal of building the officers’ confidence to handle a situation without overreacting. Captain Blanch commented that “basic attitudes are difficult if not impossible to change, but that behavior patterns resulting from those attitudes can be changed through proper training.” 2Ibid.

But did the reforms work? Were police able to change their racist behavior patterns through proper training? A look at the history of the decades since suggests the answer is no, and that these reforms was just another in a long series of attempts to fix a system that is rotten to its core.

1.League of Women Voters of Minneapolis, The Police and the Community, a second look (Minneapolis: The League), 1976.

2.Ibid.

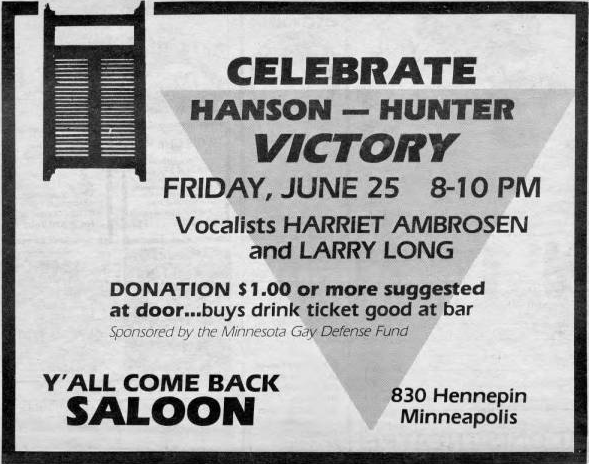

Homophobic Cops: Attacks on Minneapolis’ Queer Community

“The case was atypical in that the jury didn’t buy the police version of the story.”1Tim Campbell, “Jury Acquits Hunter and Hanson of All Wrongdoing.” GLC Voice, 7 June 1982, 1.

-Tim Campbell, 1982

On January 1, 1982, Rick Hunter and John Hanson were taunted and threatened by two men outside a popular Minneapolis gay bar, the Y’all Come Back Saloon (the Saloon). The threats escalated when a man named Richard Corum jumped out of his car saying ‘they “were going to kill [those]…faggots.”2Paul Klauda, “Gay Men complain police beat them,” Minneapolis Tribune, 14 January 1982, p. 1B Hanson, who worked part time as a bouncer at the Saloon, punched Corum and a fight began. Police arrived on the scene and threw Hanson against a wall, choked and beat him around the head. When Hunter cried out, three officers threw him to the ground and beat his head against the sidewalk before ordering him to drop the champagne bottle police later said Hunter was “carrying in a menacing manner.”3Ibid. In the words of witness Sheryl Stark, the police beat Hanson “over and over and over again. I just couldn’t believe it.” 4Campbell, “Jury Acquits Hunter and Hanson of All Wrongdoing,” 1.Hanson and Hunter were arrested and charged with assault, disorderly conduct and interfering with arrest. 5Ibid. Unlike most cases of gay bashing, which were routinely ignored in papers, the Minneapolis Tribune reported this case, because Hunter and Hanson filed a complaint against the “at least four police officers” who assaulted them.6Klauda The case made headlines again in May of 1982, when Hunter and Hanson were acquitted of all wrongdoing by a straight-identified jury.

The Minneapolis gay community had long been aware of the subtle–and not so subtle–mistreatment of homosexual people by the police department.

An ad for the Saloon, a long-standing cornerstone of the LGBTQ community in Minneapolis. The Saloon frequently held legal defense fundraiser and to raise money to get the charges against Hanson and Hunter dropped.

Although gay bars were mostly safe from police through the 1950s and 1960s (some argue, as a result of mafia owners who paid off police, rather than as a result of tolerance), the 1970s and 1980s brought a change as bathhouses and gay bars were often raided. In Queer Twin Cities, community members reported these raids were often conducted by off-duty officers, after drunken nights out. One of the more widely remember events from 1979 involved a deputy mayor, who had been drinking with officers and tagged along for the “fun” of a bust. Beyond these raids, police bias against the gay community was also revealed in the way cases were prosecuted. From 1979 to 1985, over forty homosexual people in the Twin Cities Metro area died as the result of attacks aimed against them because of their orientation. Many of these murders went unsolved or were deemed accidents and so were never investigated.7Twin Cities GLBT Oral History Project, Queer Twin Cities (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010. In the 1980s, gay bookstores and their clients were also heavily targeted in police enforcement of anti-pornography statutes.8Ibid.

Gay bars in Minneapolis had been targeted on previous New Year’s Eves in Minneapolis, so the crowd at the Saloon on New Year’s Eve, 1981, was wary. Common practice in Minneapolis was to allow bars to continue operating past closing on New Year’s Eve, but police had chosen to use the violation of closing time to verbally harass patrons and owners of the Gay 90s (in 1979, resulting in a ticket to owners) and the Saloon (in 1980).

Common practice–in Minneapolis and in the rest of the country–was also to arrest the queer person who had been harassed, when police stepped in to end the fights that resulted.9Curran Nault, Queercore: Punk Media Subculture (New York: Routledge Press, 2018); and Joey L. Mogul,, et al., Queer Injustice: The criminalization of LGBT People in the United States (Boston: Beacon Press: 2011). So common was the practice that the GLC Voice summarized it this way in their writing: “The details of the case are stereotypical. Gaybashers attack peacable gays. Police arrive on the scene. Gaybashers exist. Gays get charged.”10Campbell, “Jury Acquits Hunter and Hanson of All Wrongdoing.”

At the court trial against Hunter and Hanson, the four officers testifying for the prosecution claimed that “they had no prejudice and would not have let it affect the exercise of their duties.” Bystanders at the Saloon testified they heard the police “calling Hunter and Hanson ‘faggots, queers and sissies’ throughout and after the melee.” Attendants at the emergency room, who photographed the injuries which resulted in ten stitches for Hunter and six stitches for Hanson, also testified that two of the officers “were still calling Hunter and Hanson ‘queers and sissies’ when they got to the emergency room.”11Ibid.

In the words of the GLC Voice, “this case was atypical in that the jury didn’t buy the police version of the story and in that the gays were beaten severely [by the police].”

Jury members spoke publicly about not believing the police testimony, explaining that “they know how the police will stick together on a story when they need to defend each other”They found the lack of other testimony and witnesses suspicious (Corum and his friend, the “victims” according to the police, could not be located for the trial). The all-straight jury returned a “not guilty” verdict on the 6 charges against Hunter and Hanson.

The Internal Affairs Unit had also been investigating and Police Chief Anthony Bouza exonerated the police officers involved, and they were never held accountable for the beating. Hanson and Hunter did file a civil suit, and in 1984, the City of Minneapolis settled with a payout of $750 for what was termed “minimal negligence” at the hands of the police.12Tim Campbell, “Accounts of Brutalities against Gays Rivets Panel,” GLC Voice, 19 November 1984, 1.

1.Tim Campbell, “Jury Acquits Hunter and Hanson of All Wrongdoing.” GLC Voice, 7 June 1982, 1.

2.Paul Klauda, “Gay Men complain police beat them,” Minneapolis Tribune, 14 January 1982, p. 1B

3.Ibid.

4.Campbell, “Jury Acquits Hunter and Hanson of All Wrongdoing,” 1.

5.Ibid.

6.Klauda

7.Twin Cities GLBT Oral History Project, Queer Twin Cities (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

8.Ibid.

9.Curran Nault, Queercore: Punk Media Subculture (New York: Routledge Press, 2018); and Joey L. Mogul,, et al., Queer Injustice: The criminalization of LGBT People in the United States (Boston: Beacon Press: 2011).

10.Campbell, “Jury Acquits Hunter and Hanson of All Wrongdoing.”

11.Ibid.

12.Tim Campbell, “Accounts of Brutalities against Gays Rivets Panel,” GLC Voice, 19 November 1984, 1.

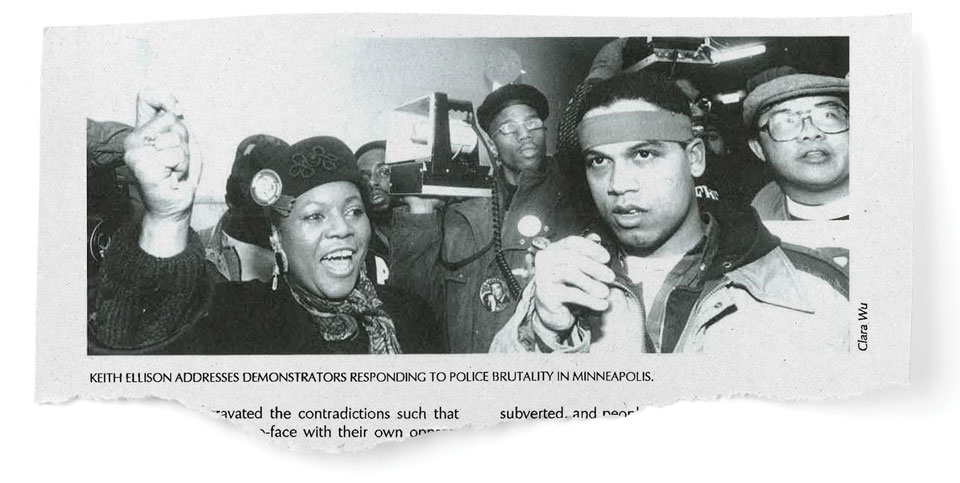

Raid Gone Wrong: The Deaths of Lillian Weiss and Lloyd Smalley

“It’s a tragedy, there are no ifs, ands or buts about it.”1Brunswick, Mark. “Retracing the raid – Survivors, police file offer clues on what went awry that fatal night,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, March 19, 1989: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47E869806850?p=AWNB.

– Minneapolis Police Department Sgt. Mike Sauro, 1989

Around 7 pm on January 25th, 1989, two Black elders, Lillian Weiss, 65 and Lloyd Smalley, 71 sat down to dinner: pork chops, baked beans, and creamed corn. Warm food for a cold night.2Ibid. They shared the table with friends; 32 year old Stuart Brunier and a close friend of his, Phillip Holloman. Brunier and his girlfriend had been evicted the previous year, and Smalley and Weiss took them in and gave them a place to stay.3Ison, Chris. “Generosity led to couple’s deaths in raid, friends say,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, January 29, 1989: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47DBA381C115?p=AWNB. After dinner, Smalley helped his partner out of her chair, mentioning to the younger men that they were going to watch “True Grit” on their black and white television. They loved spending their nights that way, curled up watching movies on two single mattresses pushed together in their bedroom. They would never leave that room.

The Crystal Police Department suspected that Brunier and his girlfriend were dealing drugs out of Weiss and Smalley’s apartment, and they asked the Minneapolis Police Department’s SWAT team (then the Emergency Response Unit, or ERU) for help executing a dangerous “no-knock” drug raid on January 25th.4Oberdorfer, Dan. “FBI asked to probe deaths in drug raid – Police actions questioned,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, January 28, 1989: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47DB81641A59?p=AWNB. Usually, that entailed breaking down the door and holding the occupants at gunpoint, searching the apartment for drugs and making arrests when possible. But this night was different: cops had received several tips that a local gang was planning on booby-trapping a crack house, setting explosives to kill officers when they tried to enter. In response, the officers planned to throw a “thunderflash stun grenade” into the apartment, entering through the window instead of through the doorway just in case the door was rigged to blow.5Brunswick 1989.

Shortly before 10, Brunier, Holloman and another friend were watching TV and falling asleep in the front room when a grenade was thrown in the window. The grenade caught a chair in the middle of the living room on fire, and the flames began to spread through the apartment. Unable to put out the fire, the officers retreated and the three men (Brunier, Holloman, and another friend) in the living room followed them, only to be quickly handcuffed. The fire department showed up minutes later. When Brunier tried to tell the police how to get to the back of the apartment, an officer put a foot to his neck, saying simply “Don’t tell me how to do my job.”6Ibid. Bystanders also tried to tell the cops and fire department about the couple still in the building, but were largely ignored.7Oberdorfer 1989. By the time the fire department made it back into the apartment, it was too late: Lillian Weiss and Lloyd Smalley laid dead on top of their bed, killed by smoke inhalation.

Brunier asked the officers repeatedly if his friends had gotten out of the burning apartment; they ignored him until, finally, on the way to police headquarters, an officer remarked, “Well, I’m not going to lie to you, your folks didn’t make it.”8Brunswick 1989.

The officers searched the burned-out apartment for guns and drugs, but after two days of searching, found nothing. That tip about gang members booby-trapping a crack house? The ambush MPD was so worried about never happened. After being arrested and questioned, Brunier and the other men who had been in the house were let go: the prosecutor had no proof they had done anything at all wrong.

The community was outraged, holding that the SWAT team would have never been so careless if they were raiding a white home. MPD had also recently profiled and brutalized a number of Black youth in an Embassy Suites downtown, and the two incidents pushed the community into action. Over the course of the next two months, hundreds of people attended a number of protests pushing for police accountability. One of the most disruptive was a protest at City Hall, where 75 people crashed a City Council meeting and then-attorney Keith Ellison read their demands to the council members.

75 people stormed a City Council meeting, in response to police brutality.

At the time, the only agencies responsible for addressing police misconduct were the MPD Internal Affairs Unit and the Hennepin County Prosecutor’s office. Both began investigations headed up by detectives from the MPD itself, co-workers of the cops being investigated. Internal Affairs quickly cleared all 18 of the officers who had been involved in the drug raid, and the criminal case went to a Hennepin County Grand Jury, which decided not to indict any of the officers.10Oberdorfer, Dan. “Officers in fatal `crack’ raid not indicted,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, March 03, 1989: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47E3FB61683A?p=AWNB. The FBI also investigated the incident, but similarly declined to file charges.11Ibid.

As 1990 began, almost a year after the raid, Lloyd Smalley’s family filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the city,12Halvorsen, Donna. “Children of man killed in drug raid sue Minneapolis,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, January 03, 1990: 01B, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47660E89A154?p=AWNB. which ended in an undisclosed settlement.13Mitchell, Cory and Furst, Randy. “Botched raid costs Minneapolis $1M – City Council approved the payout nearly two years after police used a stun grenade that left a woman with permanent injuries.,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities (Minneapolis, MN), December 10, 2011: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/13B9AC01C85170B8?p=AWNB. Community outrage at the raid pressured the city council, against the wishes of the police union, to create the Civilian Review Authority, a community-supported reform that, although meant to hold police accountable for wrongdoing, was ultimately useless.

None of the officers involved in the raid were so much as disciplined for the deaths of Weiss and Smalley. The commander of the raid, Mike Sauro, who later became one the officer at the heart of one of the biggest police brutality settlements in MPD history, described what happened to Weiss and Smalley as a “tragedy”, but quickly added that he was glad the officers hadn’t taken any chances. After all, he said, “it was a tactical situation.”14Brunswick 1989. One of the officers could have been killed. Imagine that.

1.Brunswick, Mark. “Retracing the raid – Survivors, police file offer clues on what went awry that fatal night,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, March 19, 1989: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47E869806850?p=AWNB.

2.Ibid.

3.Ison, Chris. “Generosity led to couple’s deaths in raid, friends say,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, January 29, 1989: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47DBA381C115?p=AWNB.

4.Oberdorfer, Dan. “FBI asked to probe deaths in drug raid – Police actions questioned,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, January 28, 1989: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47DB81641A59?p=AWNB.

5.Brunswick 1989.

6.Ibid.

7.Oberdorfer 1989.

8.Brunswick 1989.

9.Tai, Wendy S.. “250 marchers rally at Minneapolis City Hall – Police racism alleged,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, February 18, 1989: 01B, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47E0A4A16412?p=AWNB.

10.Oberdorfer, Dan. “Officers in fatal `crack’ raid not indicted,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, March 03, 1989: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47E3FB61683A?p=AWNB.

11.Ibid.

12.Halvorsen, Donna. “Children of man killed in drug raid sue Minneapolis,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, January 03, 1990: 01B, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47660E89A154?p=AWNB.

13.Mitchell, Cory and Furst, Randy. “Botched raid costs Minneapolis $1M – City Council approved the payout nearly two years after police used a stun grenade that left a woman with permanent injuries.,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities (Minneapolis, MN), December 10, 2011: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/13B9AC01C85170B8?p=AWNB.

14.Brunswick 1989.

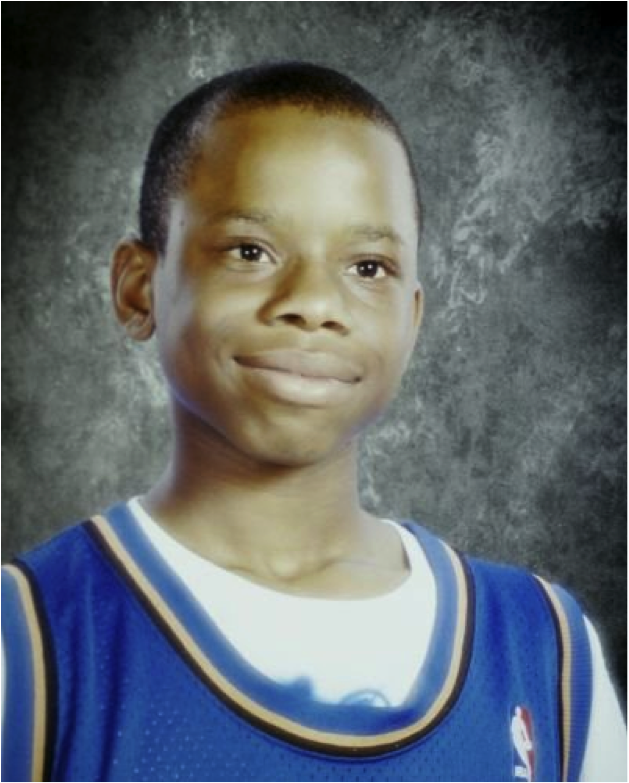

The Murder of Tycel Nelson

“It is a street-corner tableau played out with chilling frequency in city after city, often with the predictable results: controversy, protests, calls for investigations.”1Harrison, Eric. “Minneapolis Race Calm Shattered by Shooting : Civil rights: A black gang member is fatally shot in the back. Hostility simmers between police and community activists.” Los Angeles Times, February 12, 1991. August 8, 1993. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://articles.latimes.com/1991-02-12/news/mn-1357_1_police-officers.

– Los Angeles Times, 1990

Minneapolis police officer Dan May. Image from the Star Tribune via Associated Press File, 1991

On December 1st, 1990, the Minneapolis Police Department was called to a party where a fight had broken out. While they were on their way, two people were shot. When they arrived, Officer Dan May hopped out of his car with a shotgun, chasing 17 year old Tycel Nelson behind a house. Minutes later, the teenager was dead of a shotgun blast under unclear circumstances, an action that would result in widespread outrage and calls for police accountability.2Brunswick, Mark. “Police officer kills teen who allegedly raised gun at him,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, December 02, 1990: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47C826CA3962?p=AWNB.

Almost immediately, the Minneapolis Police Department put together their narrative of what happened- Tycel Nelson was a gang member, brought a pistol to the party, was possibly implicated in the shooting earlier that night, ran from the police, ignored calls to surrender, turned around to shoot at Officer May, and was shot in the chest. Police Chief John Laux cleared Officer May of any wrongdoing five days after the shooting, citing a firearms discharge board investigation that only interviewed one civilian: Nelson’s cousin, who had to give her testimony in front of the the officer who had killed Tycel.3Brunswick, Mark. “Laux says shooting of teen was justified – Ruling, remarks prompt outrage,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, December 06, 1990: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47C950084416?p=AWNB.

As with many police killings, the official story of the shooting didn’t add up. A community group known as Stop The Violence found more than a dozen witnesses who mentioned that they never saw Tycel with a gun at the party, including one who saw Nelson seconds before he was shot.4Ibid; Jones, Sumner. “Community in Shock.” Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder (Minneapolis), December 6, 1990. 5.Hodges, Jill. “Officer cleared in shooting – Grand jury brings no charges in death of Tycel Nelson,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, March 27, 1991: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE420C864758B4?p=AWNB.; Harrison, 1990. A pistol was found near Nelson’s body, but there was no evidence linking it to the prior shooting, and it didn’t have Nelson’s fingerprints on it.5Hodges, Jill. “Officer cleared in shooting – Grand jury brings no charges in death of Tycel Nelson,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, March 27, 1991: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE420C864758B4?p=AWNB.; Harrison, 1990. May claimed that he told Nelson to drop the gun, but a neighbor who was nearby only heard “there goes the son of a bitch,” followed by the sound of May’s shotgun.6Diaz, Kevin. “Tycel Nelson case settled for $250,000 – Family drops wrongful- death lawsuit against Minneapolis,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, July 07, 1993: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFD675B79585FBE?p=AWNB. A Police report indicated that they found the gun immediately after the shooting, but neighbors and other officers said that they didn’t find it until much later.7Star Tribune, “Accounts fail to end confusion in fatal shooting,” 1990; Nisan, Chris. “Medal of Valor award ignites community outrage.” Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder. January 31, 2006. Accessed November 15, 2017.

https://www.tcdailyplanet.net/medal-valor-award-ignites-community-outrage/. Even more strangely, police said they found the gun next to Nelson’s right hand, even though he was left handed. Finally, though Officer May claimed that he shot Nelson in the chest as he pointed the gun at the officer, ballistics evidence showed that Nelson was shot in the back.8Star Tribune, “Laux says shooting of teen was justified – Ruling, remarks prompt outrage,” 1990.

10.Hodges, Jill. “North Side meeting decries `police coverup’,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, December 07, 1990: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47C999ADBFAD?p=AWNB.

On December 6th, more than 600 community members, many of them youth, gathered at North High School to express outrage and discuss next steps.9Hodges, Jill. “North Side meeting decries `police coverup’,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, December 07, 1990: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47C999ADBFAD?p=AWNB. On the 8th, 150 took to the streets, marching to the site where Nelson was killed and then to MPD’s 4th Precinct headquarters.10Draper, Norman. “Protesters march at site where officer shot teen – 150 show their frustration over Tycel Nelson’s death,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, December 09, 1990: 01B, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47CA151BD0D1?p=AWNB. That night, two youth shot at a police car on the Southside; when they were caught and arrested, they claimed it as an act of retaliation for Tycel’s murder.11Jones, Sumner. “Calm does not prevail in wake of youth shooting.” Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder (Minneapolis), December 13, 1990.

Two weeks later, faced with widespread distrust from the community, the Hennepin County Prosecutor ceded to community calls for a special prosecutor, an unprecedented action in Minneapolis history.12Hodges, Jill. “Outside investigator to join Nelson probe,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, December 29, 1990: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47CE27C5ADF9?p=AWNB. The attorney who was hired, William McGee, was also the Executive Director of the Legal Rights Center. Many community members were supportive of the announcement, but other groups were less thrilled. The Minneapolis Police Federation explored legal action to try to keep McGee off the case, saying he was unqualified because he had been brutally attacked by police officers several times himself, including an incident from two years earlier where an MPD officer had called him a “goddamned nigger,” and “hit [him] so hard [he] urinated on [himself].”13Prince, Pat. “Can McGee be fair? It’s a question he has asked himself,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, December 29, 1990: 09A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47CE1F978EAB?p=AWNB. Against the wishes of the Federation, McGee stayed on the case.

Unfortunately, the appointment of a special prosecutor didn’t change the case. An all-white grand jury exonerated Dan May for shooting Tycel Nelson on March 26th, 1991.14Hodges, Jill. “Officer cleared in shooting – Grand jury brings no charges in death of Tycel Nelson,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, March 27, 1991: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE420C864758B4?p=AWNB. An investigation by the FBI also resulted in no charges being filed against May. Nelson’s mother filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the city, which was settled for $250,000 in 1993.15Diaz 1993.

That June, the awards committee of the Minneapolis Police Department recommended that Dan May receive the Medal of Valor, MPD’s second-highest honor, for killing Tycel Nelson. When the Police Chief, conscious of potential outrage, refused to award May the medal, the entire awards committee resigned in protest.16Hodges, Jill. “5 quit police awards panel – Laux’s decision on May is cited,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, July 11, 1991: 01B, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE43760900E9B4?p=AWNB. The idea of giving May a medal for the shooting was enduring; in 2006, fifteen years later, the awards committee would successfully award the Medal of Valor to Dan May, who returned it amidst renewed community outrage.17Nisan 2006.

It turns out the night Tycel Nelson was killed was not the first time he had interacted with Minneapolis Police Officers. In fact, a little more than a year before, he and six other teenagers went on a school-sponsored trip to the Boundary Waters with cops as part of MPD’s Canoe Outreach Program for “at-risk youth.”18McEnroe, Paul. “Aftermath on the avenue – Ty `had the smarts’ to rise above the street violence,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, December 16, 1990: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47CB992146A5?p=AWNB How ironic that, in the end, members of the same department would pose the greatest risk to his life.

1.Harrison, Eric. “Minneapolis Race Calm Shattered by Shooting : Civil rights: A black gang member is fatally shot in the back. Hostility simmers between police and community activists.” Los Angeles Times, February 12, 1991. August 8, 1993. Accessed November 15, 2017. http://articles.latimes.com/1991-02-12/news/mn-1357_1_police-officers.

2.Brunswick, Mark. “Police officer kills teen who allegedly raised gun at him,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, December 02, 1990: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47C826CA3962?p=AWNB.

3.Brunswick, Mark. “Laux says shooting of teen was justified – Ruling, remarks prompt outrage,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, December 06, 1990: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47C950084416?p=AWNB.

4.Ibid; Jones, Sumner. “Community in Shock.” Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder (Minneapolis), December 6, 1990.

5.Hodges, Jill. “Officer cleared in shooting – Grand jury brings no charges in death of Tycel Nelson,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, March 27, 1991: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE420C864758B4?p=AWNB.; Harrison, 1990.

6.Diaz, Kevin. “Tycel Nelson case settled for $250,000 – Family drops wrongful- death lawsuit against Minneapolis,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, July 07, 1993: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFD675B79585FBE?p=AWNB.

7.Star Tribune, “Accounts fail to end confusion in fatal shooting,” 1990; Nisan, Chris. “Medal of Valor award ignites community outrage.” Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder. January 31, 2006. Accessed November 15, 2017.

https://www.tcdailyplanet.net/medal-valor-award-ignites-community-outrage/.

8.Star Tribune, “Tycel Nelson case settled for $250,000 – Family drops wrongful- death lawsuit against Minneapolis,” 1993.

9.Star Tribune, “Laux says shooting of teen was justified – Ruling, remarks prompt outrage,” 1990.

10.Hodges, Jill. “North Side meeting decries `police coverup’,” Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, December 07, 1990: 01A, accessed November 15, 2017, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EFE47C999ADBFAD?p=AWNB.